Last November, my colleague Dan Hugger critiqued comments by Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL) about his desire for “common good capitalism” informed by Roman Catholic social teaching. Generally speaking, this is an aspiration that many at the Acton Institute share, but the specifics of what that would look like are where the real differences lie.

At the least, this demonstrates how people of good will, of the same (or similar) religious and ethical tradition, can still have divergent opinions about policy. Shared principles do not automatically produce shared prudential judgments.

In another recent speech, the senator highlights this difference again, calling for the U.S. to take on an industrial policy — where the government tries to direct the economy by favoring certain industries and companies over others — crediting trade with China for a wide array of social and economic problems over the last few decades:

Outsourcing jobs to China may be more efficient because it lowers labor costs and increases profits.

But the good jobs we lose end up destroying families and communities.

Just last year, a study found that areas of the United States that faced Chinese import saturation from 1990 to 2014 experienced drops in male employment, as well as declining marriage and fertility rates.

In communities that bore the brunt of “normalizing” trade relations with China — to put it euphemistically — we even see jumps in suicide rates and deaths from substance abuse.

For public policy makers, the common good can’t just be about corporate profits. When dignified work, particularly for men, goes away, so goes the backbone of our culture. Our communities become blighted and wither away. Families collapse, and fewer people get married. Our nation’s soul ruptures.

Liberty Fund’s Richard Reinsch responded yesterday at The American Mind with a critique that echoes one of the Acton Institute’s core convictions: life is economic, but economics is not all of life. He writes,

As in his Common Good Capitalism address last November, Rubio speaks with nationalist urgency to our problems. However, he hangs far too many of our ills on a materialistic diagnosis. Without explicitly naming it, he attributes to so-called “China Shock” (i.e., the loss of manufacturing jobs to China) the vanquishing of our families, marriages, small towns, and civil society.

If only the causality of deaths of despair, male joblessness, marriage decline, and births outside of marriage were that linear — and not the result of numerous policy, cultural, religious, and social feedback loops that stretch back for decades!

Despite his apparent support for some form of capitalism, Rubio’s materialistic thinking cedes far too much ground to Karl Marx’s claim that economic causes are ultimate and stands in contrast to the vast scope of the Christian tradition that Rubio desires to integrate into his policy-making.

Yes, economics matters — and Reinsch does an excellent job of debunking many of the false claims of contemporary economic nationalists, showing that even on that account they are mistaken — but everything else matters too.

Many people in their wedding vows promise to stay with their spouses “in riches or poverty” — are we to blame economic causes when they don’t? Even granting Rubio’s economic claims (which, again, Reinsch ably refutes), if marriages aren’t able to endure through material hardship, shouldn’t we rather ask ourselves what that says about our culture of romance, our churches’ pastoral counseling, consumerism, spiritual formation, or any other more directly relevant issues?

To reduce everything to economics is to take the Marxist posture of an answer searching for a question, almost like a self-help charlatan: “What is it that bothers you? Marriage on the rocks? Addicted to opiods? Depressed? Suicidal? Whatever it is, I know the cause: your economic condition. And I know the cure: industrial policy.”

Thankfully, people like Richard Reinsch show a better, more nuanced, and prudent way of addressing the concerns of economic nationalism.

You can read Reinsch’s article here.

And while you’re at it, be sure to read Samuel Gregg’s recent article on industrial policy at Law & Liberty here.

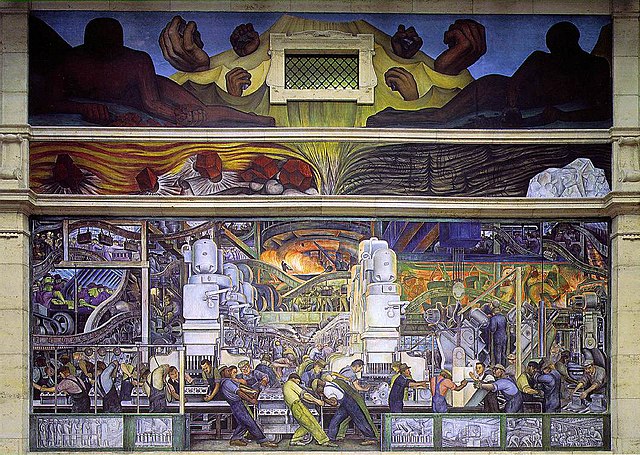

Image credit: Overview of Detroit Industry, North Wall, 1932-33, fresco by Diego Rivera. Detroit Institute of Arts. Public domain.

More from Acton

For more on Rubio’s “common good capitalism,” check out Dan Hugger’s commentary, “Marco Rubio’s myopic capitalism” here.