Despite the “America-first” claims of trade protectionists and economic nationalists, we continue to see the ill effects of the Trump administration’s recent wave of tariffs—particularly among American businesses, workers, and consumers.

Alas, while such controls may serve to temporarily benefit a select number of businesses or industries, they are just as likely to distort and contort any number of other fruitful relationships and creative partnerships across the economic order—at home, abroad, and everywhere in between.

In a recent article for Gulfshore Business, we get a small taste of this disruption as experienced by several businesses across Southwest Florida.

For Naples-based Conditioned Air, price increases have ranged “anywhere from 5 percent to 25 percent,” explains the company’s president and CEO, Tim Dupre. “For us as an air conditioning contractor, it impacted every product we use—insulation material for line sets, fiberglass and galvanized metal, to name a few.” With prices spiking well after projects had already been bid, the 385-person company has been forced to absorb the difference on behalf of their customers, amounting to $18,000 for just one recent project.

According to economist Victor Claar, an Acton affiliate scholar who is quoted in the article, such challenges are to be expected from protectionist policies. “Throughout history, free trade has been mutually beneficial for all parties concerned, and it’s lifted billions of people out of poverty,” he explains, adding a quip from one of his colleagues. “Nobody wins a trade war.”

To intentionally disrupt economic relationships, he continues, is to initiate a war “in which you start off pointing the guns at yourselves.”

“It might be politically advantageous for somebody like President Trump to claim that he’s saving American steel jobs from unfair competition from China,” explains Claar. “But the numbers behind that argument really don’t add up. I’ve seen at least one estimate that in the United States we have fewer than 149,000 steel jobs left, yet we have about 6.5 million jobs in the U.S. that depend critically on steel as an input. So, if what we care most about is the plight of our fellow American workers, we might very well be risking millions of jobs in an effort to save thousands.”

While many are quick to claim that free traders are cold and indifferent to the pains of economic disruption and creative destruction, the protectionist alternatives simply redirect such pain toward other American producers, consumers, and communities—replacing authentic market signals with arbitrary impulses and rearranging relationships based on artificial information.

As a result, such policies only serve to delay a real competitive response to the supposed economic “threats” around the globe. To the contrary, they are far more likely to signal weakness or trigger new antagonism from abroad, for after “pointing the guns at ourselves,” as Claar puts it, other countries are soon inspired to reorient their weaponry accordingly—bringing plenty of pain to Americans from the opposite direction.

For example, China’s retaliatory tariffs are already having a significant impact on Florida’s citrus growers and other key exporters to China:

In 2017, the last year data was available for the report, Florida exported $3.5 billion in services to China. Between goods and services, the report estimated that exports to China from the State of Florida supported 36,280 U.S. jobs.

“Most of the impact has been to California’s fresh fruit sales,” says Steve Smith, executive vice president of the Gulf Citrus Growers Association. “There’s a secondary impact in our area because the lack of sales to China from California has caused the fruit to saturate this market, and that’s backed up inventory and depressed prices.”

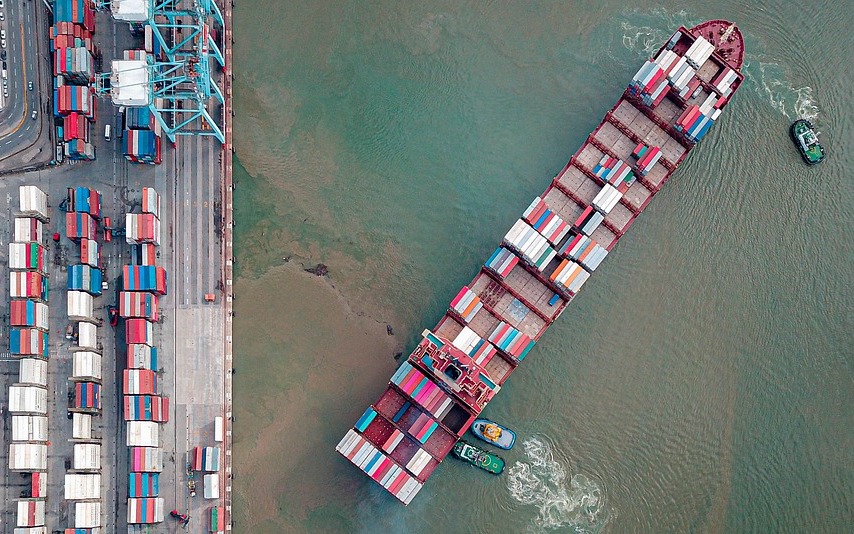

Despite their supposed aims, protectionist policies have done a poor job of protecting American workers and businesses. Instead, we see the severing of intricate supply chains and longterm relationships, as well as confusion among local producers as to what, exactly, they ought to produce, and for whom they ought to produce it. “It’s not a simple matter of are you for trade or are you against trade? Are you for China or are you against China?” says Doug Barry of the U.S.-China Business Council. “Our economies are very much intertwined in ways that most people don’t understand or appreciate.”

Indeed, beyond any threats to material wellbeing and economic growth, such damage points to the erosion of something a bit more profound. Taken together, the various fluctuations, surpluses, and saturations all point to a disruption in human relationships. When it comes to what occurs within and throughout those relationships, it isn’t just the simple transfer of material stuff—and that’s true from the bottom to the top, from the local to the global, from the tangible to intangible.

Expanding opportunities for trade is simply expanding opportunities to connect the work of our hearts and hands to those of our neighbors through creative service and collaboration. Conversely, hindering those opportunities doesn’t just provoke and strain relations or lead to less efficiency—it cuts off paths for creative collaboration among real, creative people, disrupting a diverse, peaceful, and productive web of human relationships.

As we continue to assess our trade policy, the wellbeing of this or that domestic industry or business or worker group is important. But it ought to be considered in the context of those greater circles of exchange—oriented not around serving the interests of the few, but empowering human creativity and expanding human collaboration in pursuit of an improved whole.