The Venezuelan people continue to struggle and suffer under the weight of severe socialist policies, facing economic collapse, widespread poverty, and mass starvation.

In response, socialism’s critics are quick to focus on the external features, noting how all of this could have been easily avoided with a basic respect for property rights, free exchange, free prices, and so on. But while the economic drivers and indicators deserve plenty of emphasis, we should also be mindful of the deeper effects of socialism, which reach well before and beyond economic catastrophe.

According to Jorge Jraissati, a Venezuelan economist and political leader, the suffering of the Venezuelan people is a clear reminder that socialism doesn’t just fail as an economic strategy; it also fails as a vision for the human person—sowing seeds of oppression and social unrest.

“As a Venezuelan and an economist, I believe we economists sometimes need to go beyond economic indicators,” writes Jraissati. “We need to speak from our hearts about our experiences. Only by doing this can we truly communicate the social implications of an economic collapse of this magnitude. No economic indicator could ever do justice to the depth of the human suffering taking place in Venezuela today. Venezuelans are suffering in ways most people in developed nations could not even imagine.”

Such suffering began with a broader shift in the country’s priorities. In the years before Hugo Chavez, Venezuela was in better shape than much of the continent. Then, as Jraissati explains, leaders began to elevate the goal of material equality over the preservation of individual freedom:

On February 4th, 1992, Hugo Chavez led a failed coup d’état. That day, people died, and democracy moved one step closer to extinction. While the majority of Venezuelans defended their democracy by condemning Hugo Chavez’s actions, a growing sector applauded the coup. Former President Rafael Caldera was one of them. He argued that democracy meant nothing if people were hungry. His statement, in a resource-rich country with a history of militarism, represented the dangerous idea that human freedom was less important than material well-being. Caldera’s idea resonated with a large portion of the country, and it was partially responsible for the election of Hugo Chavez as president in 1998. In a Latin American context, this is a primary reason that our nation seems allergic to economic prosperity. In Latin American, material egalitarianism, as a political doctrine, has condemned our nations to higher levels of poverty, inequality, and injustice.

Alas, for all of the common critiques about capitalism as a mechanism for materialism, few seem to recognize that a different variety of materialism forms the very foundation of a socialistic system. Though “equality” may be the more commonly professed value, material allocation is necessarily at the center of it all. And society which focuses solely on the surface-level material stuff is sure to be emptied of all else.

Which is why Jraisatti’s bigger lesson isn’t just for Chavistas and so-called “democratic-socialists.” It applies to anyone who might be tempted to see human relationships only in terms of their output.

While capitalism may, indeed, lead to better economic outcomes, it brings its own variety of temptations. It can be easy to focus only on the surface-level economic successes, relishing in any number of metrics and convincing ourselves that material prosperity is the ultimate aim. Without a more foundational embrace of freedom as a good in itself—and of human dignity as something worth affirming regardless of economic circumstances—we risk a similar drift into materialism.

Even for those who reject socialism and proclaim the goodness of economic freedom, our priorities need to be ordered by something deeper and wider than simply boosting GDP, as good a goal as that may be. If they aren’t, Jraissati explains, we’re bound to see disconnect and destruction across the other spheres of society—political, social, religious, and otherwise:

Human dignity demands to be recognized through political, social, and economic freedoms—freedoms that are completely absent in Venezuela’s current political framework. Venezuela represents much more than an economic case study. It is a reminder of the immeasurable value of freedom in itself.

I think we often make the mistake of supporting free institutions solely for their economic results. Free and open societies do enable us to achieve individual and collective socioeconomic development, and that is important. However, utilitarian arguments are not enough. We must communicate why our ideas lead to a more just society.

Socialism fails as a philosophy for economic wellbeing, but that’s because it fails as a philosophy of life—based on a cramped, contorted vision of the human person.

If we hope to avoid the failures and human suffering currently on display in Venezuela, we will need more than the removal of authoritarian rulers or a recognition of the economic merits of “pro-market” policies or even a shift from public to private ownership (though all of this will surely help).

More fundamentally, we need to recognize the dignity of the human person and embrace the moral good of freedom in and of itself.

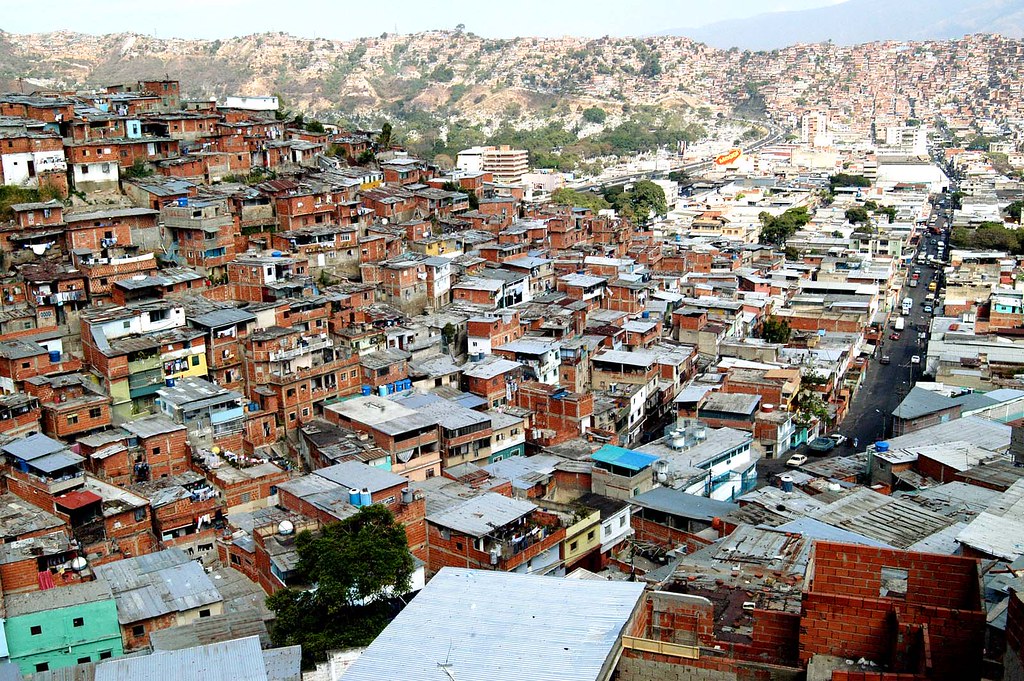

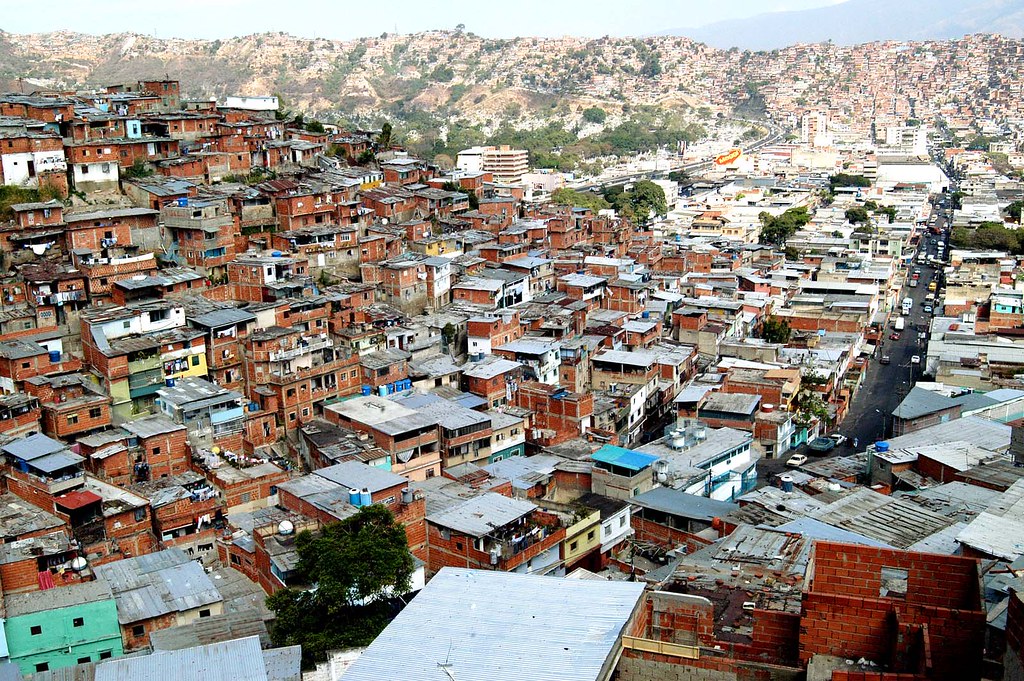

Image: Vista de los Cerros de Caracas, Fraymifoto (CC BY 2.0)