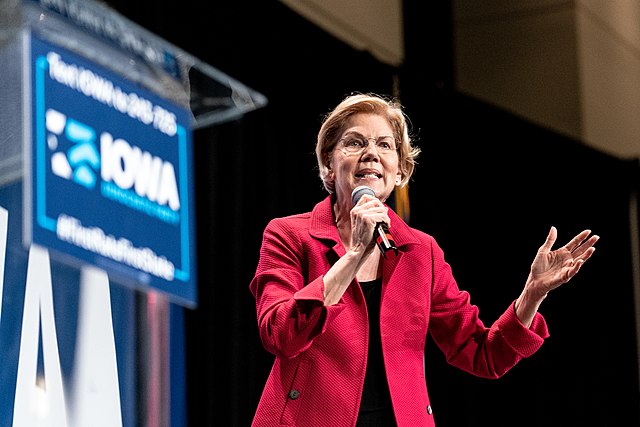

In the past few weeks, democratic presidential hopefuls outlined income inequality fixes anywhere from $1,000 per month basic income to free college and single payer healthcare. While many operate on the assumption that income equality results in a fair economic system, I do not. A fair economic system allows for a level of income inequality, and policies that force income equality not only create economic havoc but are not even biblically required. And religion, invoked by both Pete Buttigieg and Elizabeth Warren, sets the American compass for economic relief policies.

Anne Bradley, Vice President of Economic Initiatives at the Institute for Faith, Work, and Economics, argues in Counting the Cost: Christian Perspectives on Capitalism that, “Income inequality is an economic reality manifested from the biblical principle of uniqueness.” Genesis 1 tells us we are created in the image of God. That gives every person dignity, regardless of their income. A core belief in Catholic social thought is that dignity does not come from ones income, but from their personhood.

Income does not confer worth biblically. For example, the Christian neurosurgeon can look at the janitor for who he truly is. Instead of seeing the janitor for his level of income, the neurosurgeon sees him as a creation of God with inherent worth, dignity, and potential. This principle, of course, also applies from the janitor’s perspective.

Is income inequality between the neurosurgeon and the janitor acceptable? Yes, however, we should consider what broader contexts might cause income inequality, as well as an additional response from the Christian tradition.

First, the law of supply and demand in the market tells us so. The skills of neurosurgeons are low in supply and high in demand. This makes the services of neurosurgeons much more costly than that of the janitor whose skills are more common. Therefore, it is fair for the neurosurgeon and the janitor to have income inequity, as it reflects their differing skills, talents, and abilities.

Second, both of their occupations are interdependent. The neurosurgeon could not operate in a dirty facility, and the janitor would have nothing to clean if the neurosurgeon didn’t utilize the facility by performing his job and bringing in clients. Their inter-dependency must be recognized to properly understand the disparity in income level.

Third, an individual’s stewardship can also contribute to income inequality. For example, in the parable of the talents in Matthew 25, the moral of the story isn’t centered on differing levels of resources, it is how well each person stewards the resources they are given. The parable presumes there is equal opportunity afforded to each character of the story, but it does not teach that each will have equal outcomes regardless of their stewardship.

It is important to make a distinction between the aforementioned just income inequality, and an unjust income inequality. A capitalistic society provides imperfect people the opportunity to participate fairly or unfairly. Activities such as cronyism, exploitation, racism, and sexism, amongst others, are both unjust and intensify income inequality. For example, cronyism creates a market that is overpowered by special interests. When corporations collude with the government for special favors the market does not operate in an organic way.

It is evident to see that income inequality, when arising naturally, is a manifestation of both the nature of capitalism and the biblical principle of uniqueness. We must guard against any kind of unfair and unjust practice that exacerbates income inequality. This is why one could argue that it is necessary for a free market capitalist to have an underlying ethos, or moral compass. The constructive thing about the market is that it creates the opportunity for individuals and societies to thrive. Our focus should not be on whether the rich are getting richer, but whether or not the poor are getting richer. If I could share one thing with the 2020 democratic presidential nominees it would be this witty phrase from Art Lindsey in Counting the Cost: Christian Perspectives on Capitalism: “An argument against abuse is not an argument against use. A half-truth taken as the whole truth becomes an untruth.”

Photo Credit: Lorie Shuall (CC BY-SA 2.0)