The membership of the Roman Catholic and Lutheran churches will fall by half in Germany by 2060, experts forecast. Most of that will be due less to Germans’ low birth rate than to Christians actively renouncing their religion.

The number of Catholics and Lutherans will drop from 45 million today to 22.7 million in a generation, according to a new report commissioned by the Catholic German Bishops Conference and the Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD).

The writing has been on the wall for decades. Between 205,000 and more than half-a-million people have filed the necessary government paperwork to leave the two communions every year since 1990.

The church tax creates a perverse incentive

They have to file an official form, known as an Anmeldung, to opt out of the government’s church tax, the Kirchensteuer.

At baptism, children become enrolled members of one of these two churches, or a handful or other Christian or Jewish communities that have signed up for the tax. Once children reach working age each German state, or Bundesland, deducts between eight and nine percent of their income and transfers it to church leaders.

For acting as an intermediary, the state takes its own cut from the collection plate.

Those who want to leave the church, a process known as Kirchenaustritt, must pay the government another €30 fee.

Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI criticized the bishops’ decision to impose “automatic excommunication of those who don’t pay,” calling the punishment “untenable.”

Older generations felt more inclined to pay the tax for cultural reasons but a new, more secular generation has no qualms opting out, and saving money.

The report’s lead author, Bernd Raffelhüschen, explained that “the probability of leaving is so high that this probably explains between half and two thirds of the loss of members, while demographics account for at most one third to one half.”

Church officials acknowledge that the Kirchensteuer has only made matters worse. A 2015 decision to close a loophole for capital gains income became “just the straw that broke the camel’s back for people who were already thinking of leaving,” said EKD spokeswoman Ruth Levin.

Since then, defections have hovered steadily in the mid-300,000s.

Tax plays a lesser role than the rampant secularization of the West – but poor economic decisions create perverse financial incentives for apostasy.

Empty churches, full coffers

Despite the mass exodus out of the church, the German Catholic Church’s income reached a record €6 billion ($7.1 billion U.S.) in 2017, and “the country’s 27 dioceses are” – in the phrase of the National Catholic Register – “sitting on a fortune of at least €26 billion ($31.2 billion).”

These cash infusions may have lulled church leaders into complacency. Self-described non-practicing Christians outnumber church-going Christians in Germany by more than two-to-one. A quarter of professing Catholics and one-third of Protestants don’t believe in God, one survey has found.

Some say the financial relationship has also encouraged church leaders to remain mum on distinctive Christian doctrines that run contrary to the modern zeitgeist. Most church-attending Christians in Germany support abortion-on-demand, and non-practicing Christians are nearly as likely to favor abortion as those with no faith.

“There is a fear from the side of the bishops to proclaim the truth in social-political topics since they want to avoid a hostile reaction from the [political] parties,” one concerned German told the Catholic News Agency.

Empty churches, empty cradles

The lack of faith is driving the other time bomb facing church membership – demographics – according to the Max Planck Institute for Demographics.

The German fertility rate would increase by 39 percent if German “women had the same frequency of attendance at religious services or the same attitude toward the importance of religion as women in the United States,” it found.

Demographic winter threatens Germany’s welfare state, with the tax burden of its old-age pensions and other benefits resting on an ever-dwindling tax base.

Regardless of this track record, the Catholic archbishop of Kampala has suggested importing the church tax to Africa.

At the same time, not every faith in secular Europe faces imploding membership – especially among those not participating in the church tax.

Germany’s Muslims thrive without the church tax

Pew estimates that Germany’s Muslim population of five million will increase to between six and 17.5 million by 2050.

Muslims receive no German taxpayer funding (although some extremist imams encourage their members to exploit the nation’s generous benefits as a form of “welfare jihad”). German Muslims opted out of the church tax scheme. Instead, they either pay for their own mosques or rely on Saudi funding, which has been tied to extremism.

Their independence and faith create a hope for the future that gives Muslims a higher fertility rate than native-born Germans.

The church tax has discouraged church membership, given the church a (not always undeserved) reputation as equal parts wealthy and out of touch, and potentially sapped Christians’ desire to proclaim the Gospel in its fullness to active church-goers and evangelize those outside.

The primary drivers behind Christian retreat in the West are cultural and philosophical. But when the government adds an economic disincentive, it broadens the aisles leading out of the church.

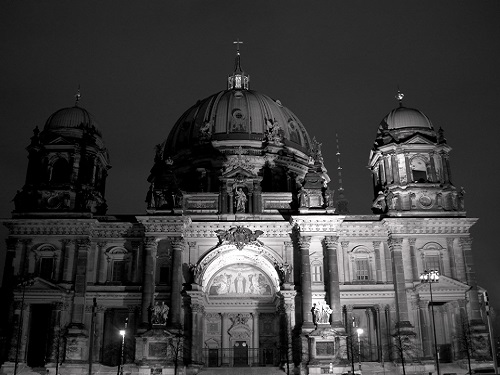

(Photo credit: Julen Chatelain. This photo has been cropped and transformed from the original. CC BY-SA 2.0.)