Our cultural environment has become increasingly defined by social isolation and public distrust, aggravated by a number of factors and features, from declines in church and community participation to concentrations of political power to the rise of online conformity mobs to the corresponding hog-piling among the media and various leaders.

Yet as public trust continues to fragment and diminish across society, there’s one institution that appears to be making a comeback: private employers.

According to the Edelman Trust Barometer, an annual study that assesses trust in various institutions, we are now witnessing a marked rise in “trust at work,” or what the researchers also refer to as the “new employer-employee contract.”

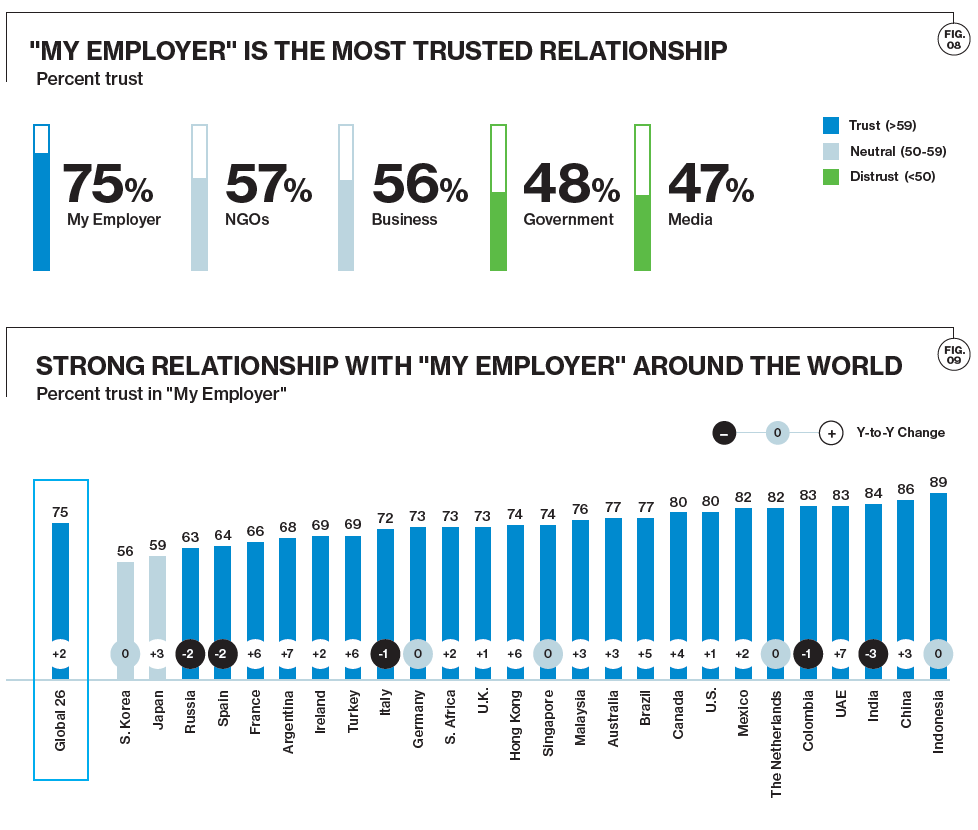

“The [study] reveals that trust has changed profoundly in the past year—people have shifted their trust to the relationships within their control, most notably their employers,” the authors explain. “Globally, 75 percent of people trust ‘my employer’ to do what is right, significantly more than NGOs (57 percent), business (56 percent) and media (47 percent).”

It’s an encouraging development on a number of levels, particularly in an age where we tend to outsource responsibilities to distant institutions and filter our social and economic problems through a top-down paradigm of social transformation and human engagement.

Such a development would seem to indicate a potential return in emphasis and orientation to the lower levels of society—to relationships and enterprises at the lower levels of “associational life.” While it would be far better if all of our institutions—government, media, and otherwise—garnered similar levels of trust, it is in a “middle layer” like the workplace where many of our greatest social contributions come alive. Whatever one thinks of top-down economic remedies, it is in the bottom-up struggle—in the give-and-take of daily creative service and exchange—where real civilizational change begins.

Yet along with this prospect of a positive shift, when assessing the study’s results a bit more closely, one will also notice hints of that same, predominant top-down paradigm. For in addition to gaining the public’s trust, employers now seem to have an expanded set of public expectations about what, exactly, they ought to contribute.

As the study reveals, individuals are not just looking to their employers for jobs, income, or new opportunities to use their gifts make a difference through improved products and services. They are also looking for “social advocacy” and “information about contentious social solutions”:

Fifty-eight percent of general population employees say they look to their employer to be a trustworthy source of information about contentious societal issues. Employees are ready and willing to trust their employers, but the trust must be earned through more than “business as usual.” Employees’ expectation that prospective employers will join them in taking action on societal issues (67 percent) is nearly as high as their expectations of personal empowerment (74 percent) and job opportunity (80 percent).

The rewards of meeting these expectations and building trust are great. Employees who have trust in their employer are far more likely to engage in beneficial actions on their behalf—they will advocate for the organization (a 39-point trust advantage), are more engaged (33 points), and remain far more loyal (38 points) and committed (31 points) than their more skeptical counterparts.

In addition, 71 percent of employees believe it’s critically important for “my CEO” to respond to challenging times. More than three-quarters (76 percent) of the general population concur—they say they want CEOs to take the lead on change instead of waiting for government to impose it.

In response, Axios ran with a headline that captured the underlying attitudes rather well: “CEOs under more pressure to save society.”

Whatever one thinks of the core role and function of a business, this expanded focus on societal-issue embellishments highlights an interesting phenomenon in modern attitudes, some of which hearken back to those same preferences for top-down action and control. “If we are to change the world for the better, surely we must run to the levers of organized bureaucracy, whether manifested in governments, NGOs, or businesses.”

But should we?

In one sense, it’s good that the public would trust their employers and CEOs with “taking the lead” on social and cultural problems—particularly if our only other option is “waiting for government to impose it” (hint: it isn’t). As I recently argued, Patagonia’s recent decision to donate $10 million in tax breaks to climate change represents a far better approach for public advocacy and debate than outsourcing such a cause to the federal government—whatever one thinks of its merits of Patagonia’s particular cause or approach.

At the same time, our personal desires or opinions about the need for “change” or “advocacy” on “contentious social issues” (pick your personal emphasis) is neither the primary focus nor the full extent of most business’ core contributions, and our “trust” in such enterprises shouldn’t hinge on how closely they mimic our personal preferences about global problems.

Thus, given the prominence of our top-down proclivities, it’s worth reminding ourselves that, even if we manage to break free from the constraints of government power or incompetence, the muscle of corporate America (or academia or NGOs or otherwise) are not the only remaining pegs on the proverbial ladder of subsidiarity and social responsibility.

Indeed, our trust in our employers and business leaders—and our expectations that they “change the world”—ought to be paired with an acknowledgement of our own responsibility and stewardship therein, wherever we fall on the supply chain or organizational chart.

We, as employees and citizens, also have a significant influence in shaping our enterprises and facilitating change through our creativity, collaboration, and contributions, playing our own role in the restoration of public trust. We are not only looking to corporate executives (or senators or presidents or scientists or celebrity activists) from the top-down. We are actively pursuing that change from the bottom up.

Our modern challenges of isolation and social fragmentation will be difficult to overcome, but returning our attention and focus to our personal spheres of influence, economic and otherwise, is a welcome sign of improvement. As we do so—seeking to revive “associational life” in business and beyond—let’s remind ourselves of our own simple yet profound role in “changing the world,” and take comfort in our freedom to respond accordingly.