Why would a lay Dominican woman from the so-called “dark ages” have any lasting relevance in today’s world?

For one reason, Catherine of Siena, was no ordinary woman. And she eventually became no ordinary saint. She was the saint of “burning love” for her passionate sense of service, reform and justice. It was St. Catherine who famously said: “Be who God meant you to be, and you will set the world on fire.”

Her infectious magnanimity and heroic life of virtue alone is a timeless gift for all of humanity.

Born in 1347 while the Black Death ravaged her city of Siena and the rest of Europe, wiping out one-third of its population, St. Catherine grew up a spirited, strong-willed daughter of an entrepreneurial father whose cloth dying business earned the family a comfortable living. Joining the third order of the Dominicans as a teenager, she became a tireless caregiver of the sick and poor and was a charismatic spiritual counselor to both clergy and nobility.

Most importantly, Catherine grew to become an expert in diplomacy and negotiations at a time when Rome’s very future hung delicately in the balance of schism and self-destruction.

St. Catherine is a patron saint of Rome, for without her, Rome may have ceased being the Eternal City.

It was during her lifetime that Rome had been officially abandoned as the traditional Capital of Christianity. Since St. Peter the Apostle, Rome was the center of moral and spiritual rule over all of Christendom. However, in 1305 – four decades before Catherine’s birth and when bishop Raymond Bertrand de Got was elected Pope Clement V – Western Civilization took a detour: all the roads that had previously lead to Rome, now headed north to the Avignon, in what is now France, but then in the Kingdom of Arles.

Refusing to move to a factious, back-stabbing Rome, the new French pope chose to remain safely in Avignon. The papal Curia eventually transferred its residence to this small Frankish town in 1309. After this year, six other popes were legitimately elected and stayed in Avignon until 1376.

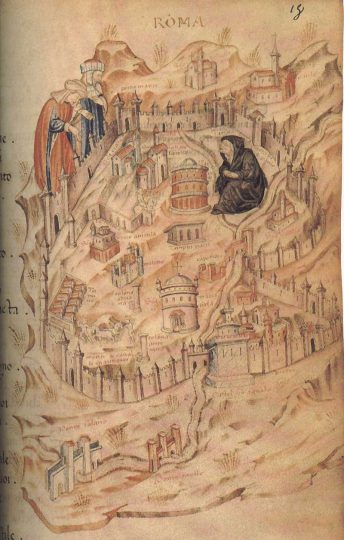

By the middle of the 14th century, a pope-less Rome had become a ruinous slum of looters, abject poverty, and festered in contagious disease. The Eternal City became the Forgotten City – the abandoned Black Widow – tail spinning out of control into economic, political and moral decrepitude. Its population was decimated: the city had dwindled to a mere 50,000 and eventually reached an all-time low of 20,000 inhabitants during the ensuing Western Schism that began in 1378.

In brief, throughout the 14th Century, while many great medieval Italian cities like Florence, Siena and Pisa eventually rose to become economic and political powerhouses, Roma caput mundi was reduced to a sickly village. It appeared destined to die.

St. Catherine reacted with righteous indignity, especially after Gregory XI became the seventh pope to reject a dangerous Rome for a more comfortable and protected life in Avignon. The unintended consequence was that Avignon popes – just like the previous Roman pontiffs – had effectively once again became political puppets to local crowns and power-positioning nobility. The Church had again grown passive, was manipulated by lust for power, and thus relinquished her true sovereign freedom.

What did Catherine do? She began a furious letter writing campaign to Gregory XI during the last part of her life in order to convince him to have his pontificate reestablished in Rome. Surely emulating the persistence and salesmanship of her entrepreneurial father, St. Catherine pulled off a feat for the ages, helping to end 70 years of the Church’s exile in Avignon, a period in the Church historians call the “Babylonian Captivity”.

With laser-focused attention on the just goal to be achieved for the common good, she would not “take no for an answer” from a stubborn Gregory XI. She pleaded with and charmed the pope with her personal affection while insisting on his moral courage and giving clear and urgent reasons.

Catherine’s convincing words are found in one of her more noteworthy letters (n. 74), where she argues to fight not evil with devilish evil, but with the power of saintly virtue:

I am begging you, I am telling you, my dear babbo ( “dad” in the Tuscan dialect), in the name of Christ crucified, to conquer with kindness, with patience, with humility, with gentleness the wrongdoing and pride of your children who have rebelled against you their father. You know that the devil is not cast out by the devil but by virtue. Even though you have been seriously wronged—since they have insulted you and robbed you of what is yours—still, father, I beg you to consider not their wrongdoing but your own kindness.

Up, father! Put into effect the resolution you have made concerning your return…You can see that the unbelievers are challenging you to this by coming as close as they can to take what is yours. Up, to give your life for Christ! … Why not give your life a thousand times, if necessary, for God’s honor and the salvation of his creatures? That is what he did, and you, his vicar, ought to be carrying on his work. It is to be expected that as long as you are his vicar you will follow your Lord’s ways and example.

St. Catherine’s optimistic persistence finally paid off. In September of 1376, Pope Gregory XI packed up and left Avignon. He headed back to Rome, even while his papal fleet battled fierce storms at sea and faced constant threats from Avignon.

Gregory XI arrived in Rome on January 17 of 1377, dying just one year later.

The rest is history, as they say, even if for the next forty years Rome had to endure further battles of power struggle while contesting claimants to the papal throne – the anti-popes – were illegally elected in the court of Avignon which refused to recognize the restored line of popes in Rome.

The tumultuous Western Schism, which at one point culminated in three simultaneous claimants to the papacy, ended with the Ecumenical Council of Constance (1414–1418) and the unanimous, uncontested election of Pope Martin V.

Less than a century later, in 1506, the construction of a new magnificent St. Peter’s Basilica had begun. The revived center of Catholic worship, whose famous dome was designed by Michelangelo, effectively paved way for Rome to raise her head proudly out of sinking despair. Rome was reborn into what is today’s 4,000,000 energetic metropolis – full of joyous creativity, zealous faith and steady commercial enterprise.

Today’s Rome, no doubt, was saved from an early death, thanks to St. Catherine, the daughter of a gritty and determined Tuscan entrepreneur who herself had fought with the same skills to negotiate the Eternal City’s righteous return as the Church’s home-sweet-home.

Note: To hear more about the heroic life of St. Catherine of Siena, come to or watch on-line Acton’s December 4, 2018 Rome conference Freedom, Virtue, and the Good Society: The Dominican Contribution.