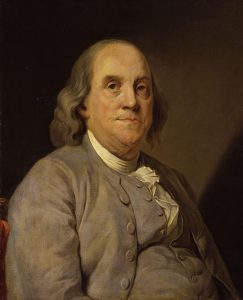

Not one of Benjamin Franklin’s better-known works, but one worth reading nonetheless, is a brief 1751 essay called Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind, Peopling of Countries, &c. Franklin covers a lot of ground in just a few pages, and brings up quite a few ideas worth commenting on, but I wanted to highlight one paragraph and its relevance for the “birth dearth” we see in the West today. Franklin explains,

Not one of Benjamin Franklin’s better-known works, but one worth reading nonetheless, is a brief 1751 essay called Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind, Peopling of Countries, &c. Franklin covers a lot of ground in just a few pages, and brings up quite a few ideas worth commenting on, but I wanted to highlight one paragraph and its relevance for the “birth dearth” we see in the West today. Franklin explains,

“Home Luxury in the Great, increases the Nation’s Manufacturers employ’d by it, who are many, and only tends to diminish the Families that indulge in it, who are few. The greater the common fashionable Expence of any Rank of People, the more cautious they are of Marriage. Therefore Luxury should never be suffer’d to become common.”

First we should note that Franklin unequivocally considers population increase a good thing—not exactly what we hear from many quarters nowadays. Franklin explains many potential hindrances to population growth, but I wanted to pause over his comments on luxuries because they seem particularly applicable to our increasingly childless society.

Franklin says that too great an indulgence in luxuries leads to a materialistic outlook and being “cautious of marriage.” I think he is largely correct. Why are children inexpedient today, and what has taken their place? Why is our age seemingly more “cautious of marriage” than any prior age? Is it perhaps because the “luxuries” Franklin warns of have become so widespread? The question goes beyond economics to culture.

In our prosperity, basic survival is a given for most. The culture encourages rather the pursuit of “fulfillment,” which is presented in many different ways. Career, accomplishments, travel, the iPhone X, sexual freedom…we may have heard all this before, but it’s good to bring up again because it has profound consequences in the long run. The idea of marriage has devolved into individualistic expectations of “romance,” which is just another species of material fulfillment. Marriage, and even stable relationships, are not in vogue. Add easy access to birth control, and the consequences aren’t hard to predict.

On top of this, consider the pervasive and annoyingly persistent idea that population growth is an evil to be avoided. Such an attitude goes back a long way—see a certain Thomas Malthus, or even farther back, Tertullian—but for the past few decades it has been standard fare in the West. It can’t be denied that this has had an impact.

Another factor, one that includes economic considerations, is a common conception that today children are simply harder to afford. This is true in the limited sense of their not being an asset in the same way they were in agrarian societies of yesteryear, but doesn’t give the full story. The wealthiest countries, for instance, are where birth rates have tended to drop the most. I wonder if it may not be more accurate to say that many in wealthy countries choose not to afford kids. What’s more important, a child or an exotic vacation and a new car? Not that there’s anything intrinsically wrong with those—I’m simply pointing out that children may have more competition than they did in the past, and the competition is winning out.

Children are counted as one “luxury” among many, and sometimes even considered the first luxury to get rid of. When I was in grad school, one of my professors posted some stats measuring the environmental impact of a bunch of different behaviors—having one fewer child, having no car, skipping a transatlantic flight, going vegetarian, drying your clothes on a clothesline, and on and on and on. In the end, the post counseled, if you’re going to do one thing to reduce your carbon footprint, have one fewer child! Or none at all. Aside from the reductionism of such an approach (for instance, Aleksandr Stoletov invented the photovoltaic solar panel—imagine if his parents had decided to not have him in order to reduce their carbon footprint), this is where materialism and radical individualism lead. When luxuries are what’s important for our own ideas of fulfillment, children become an inconvenience, an inconvenience that society teaches us to feel good about avoiding.

The fundamental problem behind the demographic winter isn’t political or economic. Obviously political and economic problems are there, and improving on them will help, but we have to look to the cultural and spiritual side of the demographic crisis if we want to solve it. The West may be prosperous, but its widespread materialism is fertile ground for, well, infertility. What’s needed is a recognition of the spiritual and cultural value of the family, together with a sense of hope for the future and a less egoistic view of the present. Ben Franklin may not have foreseen our present circumstances, but I hope he would agree.

(Photo credits: public domain.)