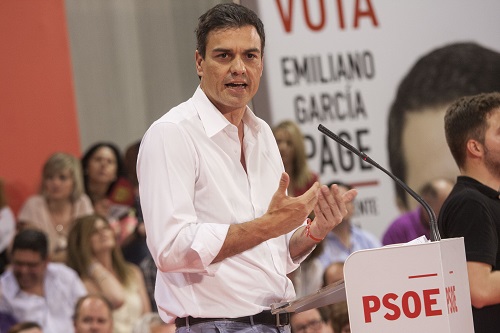

“Someone who has never won an election is now prime minister of the government,” said outgoing prime minister Mariano Rajoy, as he turned over his office to the head of the nation’s Socialist Party, Pedro Sánchez.

After Rajoy’s center-Right party, the People’s Party, had been caught benefiting from kickbacks, Sánchez called a no-confidence vote. Under Spanish parliamentary laws, instead of calling a new election, the party introducing the no-confidence vote names the prime minister’s successor within the motion.

Pedro Sánchez generously nominated Pedro Sánchez.

With the help of separatists, populist and far-Left parties, he prevailed and took office – although his party, the PSOE, holds only 84 of 350 seats.

Sanchez and his allies have long advertised their plans to socialize the economy and to crack down on the power – and siphon away the wealth – of the Roman Catholic Church. The government’s mechanism is to tax the Church for any real estate it owns that is not used for worship. Buildings where the Church carries out her philanthropic mission would be taxed.

That bifurcation of the Church’s singular mission of mercy will ring familiar to American readers. The reduction of the Christian mission to “worship,” as opposed to the free expression of religion in the corporal works of mercy, lay at the heart of the HHS mandate debate in the United States during the Obama administration.

What lies ahead for Spain?

“We will find economic and political interventionism increasing – as will state-sponsored threats to religious liberty arising from anti-Christian bias,” writes Ángel Manuel García Carmona in a new article for Acton’s Religion & Liberty Transatlantic website. “Taken together, this platform represents an attack on religion, family life, liberty, spontaneous order, and the principle of subsidiarity.”

You can read his full article here.

(Photo credit: Emiliano García Page Sánchez. CC BY-SA 2.0.)