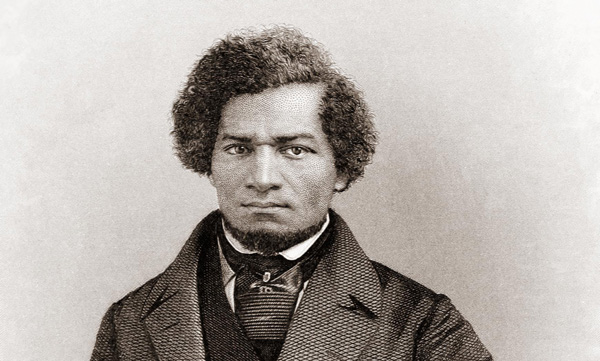

On July 5, 1852, nearly a decade before the start of the Civil War, Frederick Douglass, a freed slave and statesman-abolitionist, offered a profound speech on seeing the Fourth of July through the eyes of a slave. The speech — commonly known as “What to a slave is the 4th of July?” — illuminates the drastic disconnect between our founding principles and the severe oppression of slavery that somehow managed to endure.

While the specific evils in question have thankfully been abolished, the speech serves as a healthy reminder not only of the darker places from which we’ve risen, but how we might take care to avoid similar abuses and self-deceptions in the years to come.

Douglass’ speech offers a terrible-but-true diagnosis for a young America (only 76 years old), but it is not without its appreciation for the founders and foundations from which it sprung. Indeed, it is precisely because the Fourth of July exists that those twisted ironies are ironies.

Thus, Douglass begins with extensive exultation about the principles of ordered liberty and the “men of honesty” and “men of spirit” who sought to defend them. “I have said that the Declaration of Independence is the ring-bolt to the chain of your nation’s destiny,” he says. “So, indeed, I regard it. The principles contained in that instrument are saving principles. Stand by those principles, be true to them on all occasions, in all places, against all foes, and at whatever cost.”

For Douglass, the founding generation offered a hearty model of wise and brave resistance to naked oppression. “Your fathers staked their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor, on the cause of their country,” he says. “In their admiration of liberty, they lost sight of all other interests. They were peace men; but they preferred revolution to peaceful submission to bondage. They were quiet men; but they did not shrink from agitating against oppression. They showed forbearance; but that they knew its limits. They believed in order; but not in the order of tyranny. With them, nothing was ‘settled’ that was not right. With them, justice, liberty and humanity were ‘final;’ not slavery and oppression. You may well cherish the memory of such men.”

Alas, those who were left in the chains of slavery continued to suffer, facing severe tyranny, abuse, and violence, even as the banner of liberty and justice was wildly flown about them.

There are plenty of arguments for why such was the case, but Douglass quickly concludes that logic is not at the heart of the issue, nor should we waste our time trying to counter it in our search for solutions:

At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! had I the ability, and could I reach the nation’s ear, I would, to-day, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.

That “scorching irony” is difficult to behold, not only because the stated principles are so glaringly at odds with the reality, but because the underlying darkness is so thoroughly abhorrent in and by itself.

For Douglass, who speaks with unparalleled love and affection for the founding principles and virtues of America, those enduring violations are all the more offensive and worthy of response. “Now, take the Constitution according to its plain reading, and I defy the presentation of a single pro-slavery clause in it,” Douglass concludes. “On the other hand it will be found to contain principles and purposes, entirely hostile to the existence of slavery.”

He does not mince his words:

The existence of slavery in this country brands your republicanism as a sham, your humanity as a base pretence, and your Christianity as a lie. It destroys your moral power abroad; it corrupts your politicians at home. It saps the foundation of religion; it makes your name a hissing, and a bye-word to a mocking earth. It is the antagonistic force in your government, the only thing that seriously disturbs and endangers your Union. It fetters your progress; it is the enemy of improvement, the deadly foe of education; it fosters pride; it breeds insolence; it promotes vice; it shelters crime; it is a curse to the earth that supports it; and yet, you cling to it, as if it were the sheet anchor of all your hopes.

Though plenty of racial injustice continues to this day, the institution in question has thankfully been destroyed. We ought to celebrate that as a country, and the restoration it brings to the Declaration.

And while we should be careful not to equate or conflate or confuse the historical specifics of that atrocity with those of our own time and place, Douglass concludes with a remarkable hope and optimism that we all would do well to digest. Even at a time when slavery prevailed, Douglass found the gumption to say, “I do not despair of this country.”

In the end, Douglass found his ultimate hope not in the efforts of men, but in the power of God’s hand and the strength of the Spirit. “There are forces in operation, which must inevitably work the downfall of slavery,” he says. “’The arm of the Lord is not shortened,’ and the doom of slavery is certain. I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope.”

Even beneath and beyond that eternal light, Douglass saw a modernizing world filled with freedom and promise — one where new opportunities for human creativity and connection were bound to break age-old chains of oppression and self-protection.

In other words, the fruits of the Declaration were just beginning to bloom:

While drawing encouragement from the Declaration of Independence, the great principles it contains, and the genius of American Institutions, my spirit is also cheered by the obvious tendencies of the age….

No nation can now shut itself up from the surrounding world, and trot round in the same old path of its fathers without interference. The time was when such could be done. Long established customs of hurtful character could formerly fence themselves in, and do their evil work with social impunity. Knowledge was then confined and enjoyed by the privileged few, and the multitude walked on in mental darkness. But a change has now come over the affairs of mankind. Walled cities and empires have become unfashionable. The arm of commerce has borne away the gates of the strong city. Intelligence is penetrating the darkest corners of the globe. It makes its pathway over and under the sea, as well as on the earth. Wind, steam, and lightning are its chartered agents. Oceans no longer divide, but link nations together. From Boston to London is now a holiday excursion. Space is comparatively annihilated. Thoughts expressed on one side of the Atlantic, are distinctly heard on the other. The far off and almost fabulous Pacific rolls in grandeur at our feet. The Celestial Empire, the mystery of ages, is being solved. The fiat of the Almighty, “Let there be Light,” has not yet spent its force. No abuse, no outrage whether in taste, sport or avarice, can now hide itself from the all-pervading light.

Douglass was speaking to a young America that had plenty of remaining stains, but despite it all, he managed to see a promising foundation of liberty and virtue and start his search where ours ought to begin.

As we reflect on Fourth of July for ourselves, and respond to all that it implies, let us not just be content with the foundations from where we came, but also stay mindful of the work left before us.

Like the founding generation and the abolitionists thereafter, let us not grow passive to tyranny, even as we be sure that our resistance stays wise and prudent in the service of ordered liberty. Taking our cue from Douglass, the Declaration offers plenty of hope, and we have plenty to celebrate.

Image: Public Domain