What was China’s “one-child” policy?

In an attempt to limit population growth, China implemented a policy in the late 1970s that forbid families from having more than one child (there were, however, no penalties for multiple births, such as twins or triplets). Over the years, though, numerous exceptions have been allowed and by 2007 the policy only restricted 35.9 percent of the population to having one child.

What is the new policy?

Starting next March, a change to current family planning law will be ratified that will allow families to have two children.

Why did China implement such a policy?

During the 1960-70s, the idea of overpopulation became popularized in the West through such works as Paul R. Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb and publications such as The Limits of Growth produced by the Club of Rome. In 1978, a Chinese military scientist named Song Jian met population control advocates during a conference in Helsinki and became familiar with the work of the Club of Rome (which was, by this time, already becoming discredited in the West).

Song saw population as an issue in which he gain attention by applying his formidable mathematical skills. As Robert Zubrin says, Song “proposed that the nation’s population be considered a mathematical entity, like the position of a missile in flight, whose trajectory could be optimized by the input of a correctly calculated series of directives.”

While Song had no experience in the area of demography (he relied almost exclusively on the assumptions of Western groups like the Club of Rome), he benefited from the prestige of being a scientist in China. As Susan Greenhalgh explains, “By 1978 Song. . . had joined a small class of elite scientists, strategic defense experts whose native brilliance, signal contributions to national defense, and list of accolades from top scientists and politicians led them to speak with originality and authority on any subject and command attention.”

Based on his own formula, Song calculated that by 2080 the desired population of China would need to be about 650-700 million—roughly two-thirds of the country’s population in 1980.

The solution proposed by Song and his colleagues, as Greenhalgh says, was rapid on-childization (yitaihua). China’s then-leader Deng Xiaoping liked the idea and began implementing it as a formal policy in 1979.

How was it enforced?

The Population and Family Planning Commissions, which exist at both the national and local level, are responsible for enforcing the child restrictions. The commissions use a mix of incentives (e.g., tax benefits, preferential treatment for government jobs), punishments (e.g., monetary fines), and coercion (e.g., forced abortions and mass sterilizations) to enforce the policy.

Enforcement is reported to be lucrative for the Chinese government: Beijing has said the government collects around $3 billion a year in related fees.

What were the effects of the policy?

The direct effect of the policy, according to China’s family planners, has been the prevention of 400 million births (nearly the combined total population of the U.S. and Canada). Indirectly, the policy has lead to a massive imbalance in sex ratios.

Several years ago, in a speech before the United Nations, demographer Nicholas Eberstadt noted there is a “slight but constant and almost unvarying excess of baby boys over baby girls born in any population.” The number of baby boys born for every hundred baby girls—which is so constant that it can “qualify as a rule of nature”—falls along an extremely narrow range along the order of 103, 104, or 105. On rare occasions it even hovers around 106.

These sex ratios vary slightly based on ethnicity. For example, rates in the U.S. in 1984 were as follows: White: 105.4; Black: 103.1; American Indian: 101.4; Chinese: 104.6; and Japanese 102.6. Such variations, however, remain small and fairly stable over time.

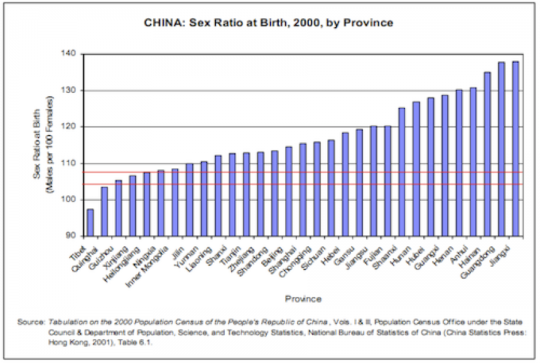

But Eberstadt found that during the last generation, the sex ratio at birth in some parts of the world—especially in China—have become “completely unhinged.” He provides this graph showing the provinces in China in 2000:

The red lines indicate where the rates should be based on what is naturally, biologically possible. Yet in a number of Chinese provinces—with populations of tens of millions of people—the reported sex ratio at birth ranges from 120 boys for every 100 girls to over 130. Eberstadt notes that this is “a phenomenon utterly without natural precedent in human history.

The reason for the imbalance is an overwhelming preference for sons combined with the use of prenatal sex determination technology and coupled with gender-based abortion. Because Chinese families were allowed to have only one child, many would simply have an abortion if it were a girl, thus keeping them from having to “waste” their quota on female children.

Why is the policy now being changed?

The change of policy is intended to balance population development and address the challenge of an ageing population, according to a statement issued by the Chinese government. The increasingly old population is a threat to economic and societal stability in the country. As Alex Coblin explains,

With nearly 120 million people over the age of 65 as of 2010, China’s elderly population is projected to more than double to nearly 300 million by 2035. China’s population aging is occurring at the most rapid pace and greatest magnitude in the world, surpassing that of Japan. Yet China’s GDP per capita on a purchasing power parity basis is only a fraction of Japan’s, barely one third; and the traditional family network, which supported China’s elderly in the past, has attenuated and will struggle to support such a large group of elderly.

What effect is the change expected to have on China?

The change is not likely to have much affect either in solving the demographic problem or in alleviating the moral horrors that have resulted from the policy.

The primary reason it isn’t likely to make much of a difference is that most Chinese citizens aren’t opposed to the policy. In fact, in 2008 a Pew Research survey found that roughly three-in-four Chinese (76 percent) approve of the policy. A more recent survey in China found that 40.5 percent said they would not have a second child, 30.4 percent said they would have another baby, and 29.1 percent said the decision would depend on the economic and family situation.

After forty years of discouraging its citizens from fulfilling the cultural mandate to “be fruitful and multiply” (Gen. 1:28), the Communist government will soon discover it won’t be so easy to reverse the effects of their immoral policy.