“Prison is a hopeless place.” That’s how one former inmate describes it. What can give hope? The freedom to practice one’s faith, even behind bars and barbed wire.

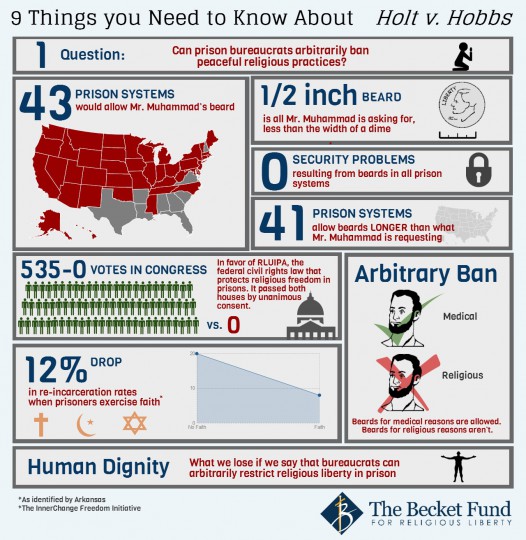

In October, the Supreme Court will hear the case of Holt v. Hobbs, which involves the following:

Abdul Muhammad, an Arkansas inmate, has been denied the ability to grow the ½ inch beard his Muslim faith commands—even though Arkansas already allows inmates to grow beards for medical reasons, and Mr. Muhammad’s beard would be permissible in 44 state and federal prison systems across the country.

The Becket Fund is co-counsel for this case, and believes that all Americans, even ones who are incarcerated, have the right to practice their religion freely. Nearly 15 years ago, Congress found that there was widespread abuse of prisoners’ rights in this area. In addition to the case sited above, there were instances of Jews not being allowed to wear yarmulkes, dietary restrictions not honored by prison facilities and the banning of religious objects such as rosaries. However, it is Mr. Muhammad’s case that the Supreme Court will hear. According to the Becket Fund website:

On June 28, 2011, Mr. Muhammad, representing himself, filed a lawsuit seeking the ability to wear a half-inch beard in accordance with his faith. Mr. Muhammad lost in federal trial court and in the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals in St. Louis. He then submitted a handwritten petition for an injunction to the Supreme Court. Justice Alito read the petition and sent it to the entire Court for decision, and the Court granted the petition. On March 3, 2014, the Supreme Court said that it would hear his appeal in full. Oral argument will take place October 7, 2014. Mr. Muhammad is now represented by Professor Douglas Laycock of the University of Virginia School of Law and The Becket Fund for Religious Liberty.

In a 2012 edition of Religion & Liberty, managing editor Ray Nothstine interviewed Burl Cain, the longest serving warden of the Louisiana State Penitentiary, or Angola. The interview, entitled “Angola Prison: A Place of Encouragement,” focused on the role of faith in a place where most of the men will never see the outside of the prison walls.

A lot of folks that come to Angola, maybe they’re buying in but hopelessness might take over, especially if they realize they’ve got no chance to get out. What are the best ways of managing that?

You just hit the nail on the head because overcoming hopelessness is crucial. The lack of hope is our greatest enemy in here. In our case, once they become moral, or once they become Christian, or once they become rooted in another faith, then they believe in the hereafter. Most religions believe in life after death. So if you believe in life after death, then it’s not hopeless here.

Yeah, your desire for God has got to kind of be greater than your desire to be free, in a sense, from a worldly perspective.

That’s right. It does. I’ve got an inmate in here and he says, “I don’t want to get out. I’m here. I’m going to be free in heaven. I want to stay here and do God’s work in prison.” And he’s a horrible murderer. He doesn’t even want to get out. He just said, “I’m here. This is a good spot for me to do God’s work. I mean, why would I want to go somewhere else? There’s plenty of work right here. It’s my mission field.” So when you get inmates that start thinking like that and talking that, you really overcome hopelessness. And he gives hope to many others.

Freedom of religion is a basic human right, one that does not disappear if a person is convicted of a crime. The practice of a faith is holistic: it is not simply attending services on a particular day of the week. It entails formal and informal prayer, often certain dress and prescribed diets and actions. To impinge on this right is a basic human rights violation.

The following infographic breaks down the Holt v. Hobbs case.