At the height of power, circa 1922, the British Empire was the largest empire in history, covering one-fifth of the world’s population and almost a quarter of the earth’s total land area. Yet almost one hundred years later, Great Britain is not so great, having lost much of its previous economic and political dominance. In fact, if Great Britain were to join the United States, it’d be poorer than any of the other 50 states — including our poorest state, Mississippi.

At the height of power, circa 1922, the British Empire was the largest empire in history, covering one-fifth of the world’s population and almost a quarter of the earth’s total land area. Yet almost one hundred years later, Great Britain is not so great, having lost much of its previous economic and political dominance. In fact, if Great Britain were to join the United States, it’d be poorer than any of the other 50 states — including our poorest state, Mississippi.

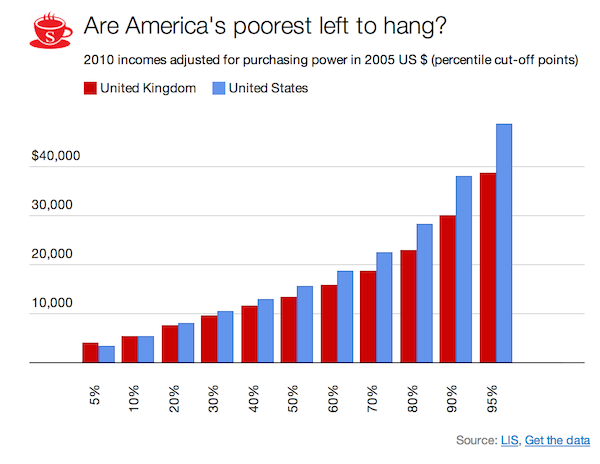

Fraser Nelson discovered that fact by using a “fairly straightforward calculation” (see the end of this article for an explanation, and what Nelson missed). The result, as Nelson explains, is that all but one income group in America is better off than the same group in Britain:

It’s not surprising that America’s best-paid 10 per cent are wealthier than top 10 per cent. That fits our general idea of America: a country where the richest do best while the poorest are left to hang. The figures just don’t support this. As the below chart shows, middle-earning Americans are better-off than Brits. Even lower-income Americans, those at the bottom 20 per cent, are better-off than their British counterparts. The only group actually worse-off are the bottom 5 per cent.

Tim Worstall notes that similar findings have shown that the bottom 10 percent in the US have the same incomes (PPP adjusted) as the bottom 10 percent in either Sweden or Finland. “While the top 10% have very much larger incomes than the top 10% in either country,” says Worstall. “All that redistribution hasn’t made the Nordic poor richer than the American poor but it has made the rich poorer.”

Unfortunately, I suspect “soaking the rich” might be the real reason many people still support redistributions schemes that go far beyond what is necessary to adequately support the social safety net for the poor. If the primary concern of redistributionists was to help the poor become wealthier, rather than making the rich poorer, they’d have long ago abandoned the idea that massive transfers of wealth is a long-term solution to poverty.

Addendum

To get Fraser’s calculation, take the US figures for GDP per state, divide it by population to come up with a GDP per capita figure and then get the equivalent figure for Britain. Finally, when comparing the wealth of nations, you need to look at how far money goes, which means using a measure called Purchasing Power Parity (PPP). Tim Worstall explains why we need to add an additional step: make PPP adjustments for the price differences between the States as well.