On November 4, 1932, the Friday before the national election that would send Franklin Delano Roosevelt to the White House, T.S. Eliot spoke for the first time as the Norton lecturer at Harvard University. He zigged immediately toward the political campaign, only to zag away from it, announcing peremptorily that the “present lectures will have no concern with politics.” And yet, though he steered clear of the campaign trail, Eliot went on to discuss the impact of poetry in ways that touch a political nerve:

The people which ceases to care for its literary inheritance becomes barbaric; the people which ceases to produce literature ceases to move in thought and sensibility. The poetry of a people takes its life from the people’s speech and in turn gives life to it; and it represents its highest point of consciousness, its greatest power and its most delicate sensibility.

That is a lot to digest at one go. We may respond by accusing Eliot of hyperbole. One may enjoy a bit of poetry now and then and yet still ask, Is it really that important? Must the “people”—I note Eliot’s Lincolnesque usage—be subject to a literary inheritance, to the dead hand of tradition, without which they will descend into barbarism? Does poetry affect how we talk, and can it possibly represent the highest point of our consciousness? What do Eliot’s warnings have to do with us? We seem to have unearthed the prophecies of an alien culture.

Eliot in 1932 was in midcareer as a poet. His phrase “literary inheritance” points back to The Waste Land, published in 1922. “Shall I at least set my lands in order?” asks the poem’s enigmatic narrator, for whom the question of inheritance extends to all the lands of the West. The phrase about a people ceasing to “move in thought and sensibility” anticipates Four Quartets, which Eliot completed in 1942. In section V of “East Coker,” the poet writes, “We must be still and still moving / Into another intensity / For a further union.” Eliot was usually interested in the unity of English and European culture, but these two passages suggest he did not stand aloof from his American patrimony.

Two questions arising from Eliot’s Harvard remarks help us frame the matter of Eliot and America. The first question is, What exactly is our “literary inheritance” as Americans? Eliot warns that we will become barbarians without it. One wonders if in 1932 it was already too late. Five years prior to his Harvard lectures, Eliot renounced his American citizenship to become a British subject. Henry James did the same in 1915, the year before his death. Eliot’s fellow modernist Ezra Pound settled in Italy. These migrations comment on a cultural inferiority complex that still rattles the more sensitive. The second question is, Do we need a literary sensibility? Is it even desirable for U.S. citizens to develop a capacity for literary appreciation outside our circle of practical concerns? Let other nations wallow in the art of poetry. We obviously prefer to pursue money and power.

Eliot’s answer to these questions requires, on our part, not only good judgment but a balance of auricular sensitivity and imagination. For instance, the phrase “a further union” suggests an allusion to Lincoln’s First Inaugural, with its summons “to form a more perfect Union.” But was this in fact Eliot’s intention, or is it a mere accident of rhetoric? We do not often pair Eliot and Lincoln in the same breath. Is there a good reason we should?

Eliot was born in St. Louis in 1888, 23 years after the Civil War and 250 miles south of Springfield, Illinois, where Lincoln’s mortal remains are buried. To Eliot and his family, the Civil War was more than a large, faceless event. His grandfather, the Saint Louis grandee William Greenleaf Eliot, founder of the first Unitarian church west of the Mississippi, lost a quarter of his congregation during the War of North and South, when he came out for a more perfect Union and for gradual emancipation of the slaves. In 1933, his grandson told an audience at the University of Virginia: “The Civil War was certainly the greatest disaster in the whole of American history; it is just as certainly a disaster from which the country has never recovered, and perhaps never will.” You will recall that in 1933 the United States was deep in the Great Depression. Eliot may have been blaming the industrial North for the economic carnage. He strongly distrusted the chaos unleashed by the American economy.

In the wake of the First World War, Eliot caricatured the Americanized West in his Sweeney poems. Here is one of my favorite quatrains, which occurs in a witty parenthesis: “The lengthened shadow of a man / Is history, said Emerson / Who had not seen the silhouette / Of Sweeney straddled in the sun.” It would not be far off to think of Emerson here as a stand-in for the Reverend William Greenleaf Eliot. Insofar as Sweeney symbolizes the Americanizing of the West, he bestrides the world like Julius Caesar. He also appears in The Waste Land. He is a victor, not a victim. To link him to the Gilded Age, to the ascendent forces of Americanization, is to follow Eliot’s suggestion that the Civil War was a disaster in its long-term effects. Eliot went on to say in Virginia: “We are always ready to assume that the good effects of wars, if any, abide permanently while the ill-effects are obliterated by time.” No doubt the audience for such commentary was more sympathetic at UVA than it would have been at Harvard.

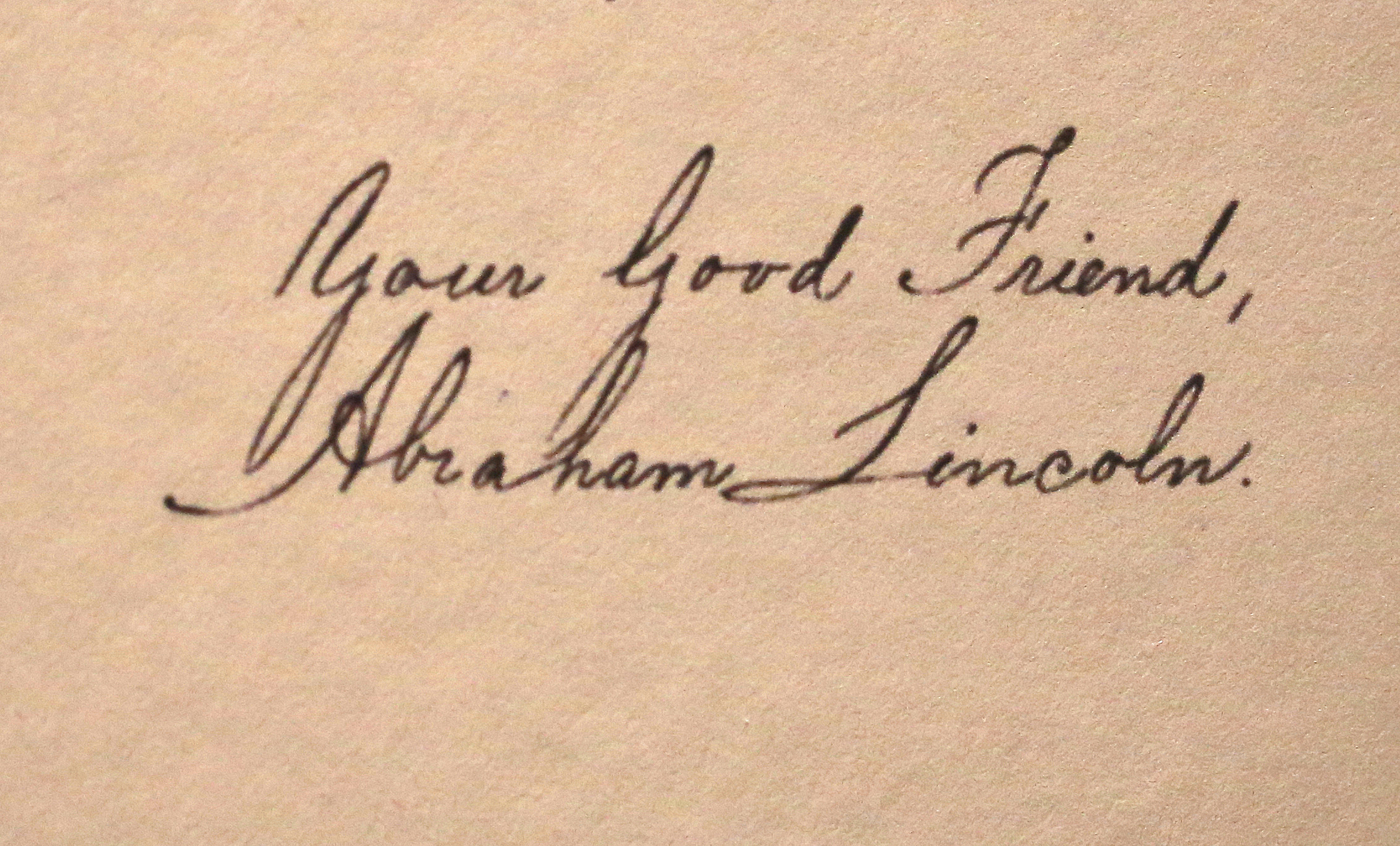

I have drawn attention to the theme of inheritance in Eliot’s poem The Waste Land. One thinks as well of his 1919 essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” which indeed centers mostly on literary inheritance. In its largest sense, the theme of inheritance, the countertheme to Sweeney and Americanization, leads us beyond the inheritance of lands and literature to the mystical contact of the living to the dead. In The Waste Land, the poet describes his being “neither / Living nor dead.” His persona Tiresias has “walked among the lowest of the dead.” In lines to which many have attributed a dominical significance, he intones, “He who was living is now dead / We who were living are now dying / With a little patience.” These passages align with Four Quartets. To quote from “Little Gidding”: “And what the dead had no speech for when living, / They can tell you, being dead: The communication / Of the dead is tongued with fire beyond the language of the living.” Now, if I were to scour American literature for the theme of inheritance prior to Eliot, I would have to pause over the Gettysburg Address. The wave-like cadences, the patterning of sound and sense, the firm command of logic, the precise emotion, both somber and stirring: As a work of art, the Gettysburg Address rivals the best political speeches of Shakespeare, and no one denies that they are poetry. For his part, Eliot, speaking in Massachusetts in 1947, named the authors of the “best classic English prose: that of Swift, Burke, of Adams and Jefferson, of Lincoln, of F.H. Bradley.” That is one powerful list, I must say, and one laden with personal significance for Eliot.

It may be that I am only imagining a literary parallel between Eliot’s poetry and Lincoln’s speech. But I am not discussing the Gettysburg Address as source material. I leave it to others to decide. I will go ahead and quote the second half of the Address, though I suspect many Americans still have it by heart:

But in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us, that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion, that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Lincoln’s reference to the “living and dead” is reinforced by a further reference to “us the living,” as well as by the mystical idea of our taking “increased devotion” “from these honored dead.” For both Eliot and Lincoln, the living must join ranks with the dead in the cause of rebirth, be it of the waste land or the Union.

Where Eliot speaks poetically of inheritance, Lincoln speaks to the American inheritance of 1776 and the Declaration of Independence. But Eliot’s case for sensibility and appreciation rests on a premise that Lincoln’s speech affirms: “The poetry of a people takes its life from the people’s speech and in turn gives life to it; and it represents its highest point of consciousness, its greatest power and its most delicate sensibility.” This is what Lincoln at Gettysburg achieves. His speech is the poetry of a people, given life and brought to “its highest point of consciousness, its greatest power and its most delicate sensibility.”

As we prepare to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the Founding, how can the conjunction of Eliot and Lincoln help us understand our own place in the grand arc of American history? How can it strengthen our vision, so that we can see ourselves as heirs, as true sons and daughters, of what we believe in? One answer lies in the tradition of thought and feeling, of reference and knowledge, that Lincoln and Eliot represent. In literary terms, this is preeminently the tradition of Shakespeare, whose work carries the legacies of Athens and Jerusalem to the American frontier. This tradition speaks with many voices, some quite surprising. It is a tradition that invites robust dialogue and genuine debate. We have a choice in the matter of what we inherit and what we toss aside. But to follow Lincoln and Eliot: The tradition survives at the cost of commitment and sacrifice.

It must be acknowledged that, in important respects, Eliot and Lincoln hold rival positions. “The ideal,” Eliot wrote in the aftermath of World War II, “is a life in which one’s livelihood, one’s functions as a citizen, and one’s self-development all fit into and enhance each other.” This statement recalls the unalienable rights, gifted by our Creator, of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. For Eliot, this ideal life faltered in America because democracy is unstable: It oscillates in practice between authoritarianism and libertarianism, with the former the likely winner in a power struggle. The War of North and South may be said to illustrate this democratic oscillation and instability. Further, Eliot was highly aware of what Jacques Barzun would refer to as the “Great Switch”: “the reversal of liberalism into its opposite.” As Washington, D.C., became our nation’s imperial center, great and necessary things were accomplished, in peace and in war. But no imperial center is without corruption on an imperial scale.

Historians will recall how, in the late 18th century, anti-federalists opposed the strong national government ratified by the Constitution. As our country developed, federalism charted a middle course by balancing the authority of national and state governments. After the Civil War, however, the system of federalism gradually retreated. The tendency was in one direction, and Eliot, whose New England ancestors went back to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, took the long view, in which the sole means of restoring a proper balance was the Church. For Eliot, only the Church harbored sufficient authority to push back against the modern superstate.

Lincoln’s understanding of church-state relations was not the same as Eliot’s. The author of the Second Inaugural was tortured by religious questions. Scholars who attribute Lincoln’s theistic utterances to political opportunism have lost the thread. On the other hand, Lincoln was not an orthodox Christian. He viewed the Founding as a signal act of Providence. On that basis, he saw himself as the instrument of a God who, in 1776, blessed the American Republic with an immanent authority such as orthodox Christianity denies to worldly princes. For orthodox Christians, Christ and Caesar must remain distinct.

And yet, Lincoln and Eliot illuminate each other. If I were to put a name on the tradition within which their affinities and differences cohere, I would call it Christian humanism. No doubt The Waste Land and the Gettysburg Address occupy a more liminal space than the term Christian might suggest at first blush. But the effects of Christian culture are not always as obvious as Christmas trees. As I have mentioned, we can see behind Eliot and Lincoln the figure of Shakespeare, an author whose world was much more Christian than professors today can typically recognize. Shakespeare’s dependence on Christianity is revealed in the glaring failure of an anti-Christian professoriate to keep his work relevant and alive. Lincoln’s speeches and Eliot’s poetry face the same crisis.

As a force for renewal, Christian humanism prefers the pen to the sword, and the power of persuasion to the power of bending others to one’s will. When the power of persuasion fails, the state can choose to embrace authoritarianism. Whenever this authoritarianism prevails, the poetry of a people can no longer take its life from the people’s speech, nor in turn give life to it. The barbarians guard the gates, and Eliot’s words at Harvard become prophetic of Harvard’s descent into sectarian strife.

(This essay is based on a lecture delivered at ISI’s American Politics and Government Summit on Nov. 8, 2024.)