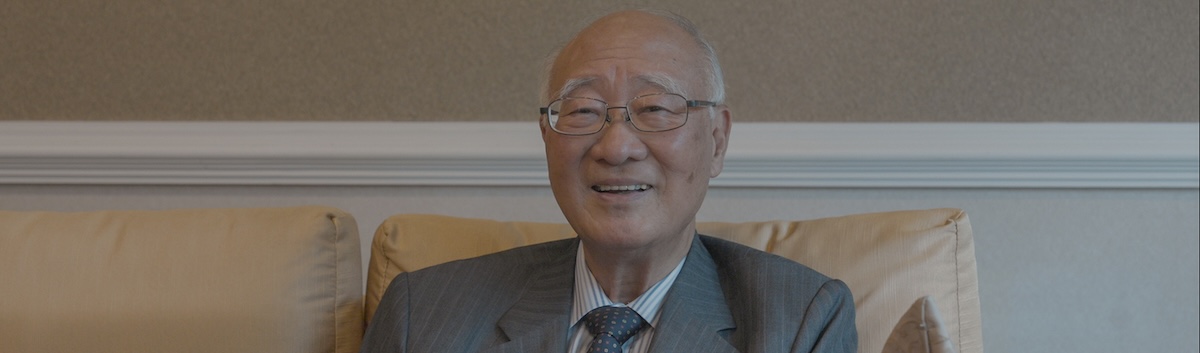

In early October, I sat down with Chou-seng Tou, former ambassador of Taiwan (the Republic of China) to the Holy See (2004–8), at his residence in Taipei. Ambassador Tou has had a long and distinguished diplomatic career. He joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1976 and served in a variety of posts in Senegal, Brussels, Greece, and Chicago, among other locales. In 2004 he was appointed ambassador to the Holy See, in the twilight of Pope John Paul II’s historic pontificate. In 2006, he was received into the Catholic faith at the Basilica of Sant’Eugenio in Rome. Now, at the age of 82, he lectures on international relations and Holy See diplomacy at Fu Jen Catholic University in Taipei.

During the interview, we engaged in a wide-ranging discussion about political, economic, and religious themes that will give Acton Institute readers a better understanding of the Goliath of Beijing in relation to the David of Taiwan in its battle for freedom, as it wages a diplomatic and ideological tug of war to maintain its sovereignty, natural rights, and liberties, and even its own cultural identity. It is also a deeply independent and religious nation, a bastion of freedom for the Catholic Church, especially now that the Vatican-China deal has been extended. Tou’s main concern is that Taiwan never become a veritable serf to the Chinese Communist Party. Nowadays, Tou warns, “You must be faithful to Xi Jinping’s thought, to Xi Jinping’s doctrine, among other things. So you are constantly encircled by this political, ideological thought.”

MATTHEW SANTUCCI: Mr. Ambassador, over the past 70 years the Church has faced many challenges in the People’s Republic of China. What are some of the main challenges today blocking formal bilateral relations between the Holy See and mainland China?

AMBASSADOR CHOU-SENG TOU: The big difficulty between mainland China and the Holy See is that the Catholic Church is under control of the Chinese Catholic-Patriotic Association (CCPA), which is under the United Front Work Department [one of the departments of the Central Committee of the CCP]. In other words, the Church is totally controlled by the state.

There have been some big changes, namely after September 2018, when both sides concluded an agreement concerning the nomination of bishops. Officially speaking, mainland China acknowledges that the pope is the only person who can nominate the bishops. Of course, the Holy See made some concessions, as it [was] important to reach the agreement, but the agreement has not been disclosed to the public. We don’t know too much about the contents.

If the CCPA and the Holy See agree on a particular candidate, there’s no problem. But the problem arises when the Holy See does not share the same view with a patriotic association. Sometimes the case will be “lead away” or either side [will] make concessions. So they still have some problems. But the importance [of] the agreement [being] extended for another period of time, two years, is that the Holy See considers so precious [the] making [of] a formal channel of a meeting opportunity [so that] the dialogue can be continued.

In 2007, Pope Benedict XVI released a letter to the Catholics in China. Do you think that the Church’s approach, with respect to mainland China, has remained the same, evolved, or has there been some sort of radical shift?

Well, the Holy See has its principles, and I think that letter was very clear in explaining the fundamental position of the Holy See towards China. Benedict XVI intended to improve relations with China, but he had his own principles. Pope Francis is a Jesuit, and as a Jesuit he has his own dream of China—think of the figure of Matteo Ricci. So he is much more active, and much more enthusiastic than his predecessors to go further, and to make more concessions, in order that at least there’s a dialogue which can be continued.

We hear often this refrain by the CCPA that they reject all foreign “involvement” in domestic affairs. How is this reflected in its strict control of religious activity vis-à-vis the deal?

Well, I want to give you a very concrete example of how the Church is under control. I just came back from a trip to the northern part of China. I visited Buddhist temples, Taoist temples, Catholic and Protestant churches. And at the entrance of every religious site, there is a sign which says persons under the age of 18 are not allowed to enter.

But when I visited the Buddhist or Taoist temple, I saw a lot of children inside, either alone or with their parents. On the contrary, in Catholic and Protestant churches, persons under 18 were strictly not allowed to enter. So that means they tolerate the local religions, but they are very strict vis-à-vis the former.

And what about the difference between Sinicization and forced Chinese inculturation? Can you highlight the difference between the two? Often there is a confusion between or even an intentional conflation of the two, one being a cultural process and the other political.

Since the Second Vatican Council, the Church has allowed for the use of the vernacular. For example, in Taiwan, even in the aboriginal area, they use their own languages. And even thinking about the construction of churches in the Chinese style, that started even before with the pope’s first delegate to China, [Cardinal] Celso Costantini. He promoted the idea that the Church should be in the Chinese style, that when [Taiwanese] enter into it, they should be comfortable. In Taiwan, you’ll see some churches that are totally westernized, while others have conserved the Chinese tradition.

So that is the effort to teach people that the Christian religion is a local church; it’s not extraneous.

It is important to note that the structures of the two societies are totally different. Here in Taiwan, it’s free, (and) the Church has sufficient room to do its work. The state did not put its hand in the different religion. So the system, the social structure, totally different. The Church has sufficient room to do its work. On the contrary, in mainland China, for a priest or a missionary, the first thing is to be a good citizen, to be loyal to the doctrine of communism, loyal to Chinese law. You must be faithful to Xi Jinping’s thought, to Xi Jinping’s doctrine, among other things. So you are constantly encircled by this political, ideological thought.

As a professor, you lecture on Holy See diplomacy and international relations. When we think of the Holy See as an international actor, how can we contextualize or better understand its unique mission?

Most people have no idea what the Holy See is. Maybe they know that it is very important in our country, but they don’t know how it works, or what their mission is. So I focus on teaching the people, telling them that the Holy See has existed for a long time and is a very important actor in international relations, especially as it relates to maintaining international peace. It’s really critical to study the role played by the Holy See, its relations with different parts of the world, and even with communist countries.

Before I went to the Vatican, I was very puzzled on how the Holy See could advocate for freedom, basic human rights, and yet deal with communist countries. But after serving for many years in the Vatican, I started to understand that the Holy See’s mission is to evangelize in every part of the world, to create an environment which is favorable to evangelization work. The Holy See’s goal is to take care of those people who otherwise have no direct connection with the Holy See.

You were baptized in 2006, in Rome. Did your appointment as ambassador to the Holy See have any role in this decision?

When I went to the Vatican, I was not Catholic; when I came back, I was. I received my baptism in the second year of my service, in 2006. Before I was appointed as ambassador to the Holy See, I asked permission from my minister to visit the seven dioceses [in Taiwan]. And I was totally and deeply moved. All the bishops, all the missionaries, sisters, whenever I met them, they gave me a feeling of peace, feeling of, how to say, tranquility, a peace of heart—I was totally moved. Once I was in the Vatican, every day I met a lot of officials from the Holy See; I had more opportunities to meet different people. The same thing happened during my visits to the Taiwanese dioceses.

When I finally made the decision to be baptized, I did not want people to make a political connection. As is customary, before Easter or before Christmas, if any member of the diplomatic corps would receive baptism, it would be by the pope himself.

I was asked if I wanted to be baptized by Pope Benedict XVI. I would have considered it the greatest honor in the world. But considering that I didn’t want to politicize the event, I informed the secretariat of state that I would have a low-key ceremony in the Basilica of Sant’Eugenio.

There are a lot of people around the world who don’t know that much about the Catholic Church in Taiwan or the diplomatic relationship with the Holy See. What one thing would you want people to know about the Catholic Church and how it relates to Taiwanese society?

I don’t know whether non-Catholics are interested in this problem, but the Holy See is very important for Taiwan, as it is the only country in Europe with which we have full bilateral diplomatic relations. And I appreciate that the Holy See adheres to its principle of religious freedom and respect for basic human rights, and advocates for fraternity, love, peace.

It’s important to note that our relationship with the Holy See is a triangular relationship, as it not only concerns our bilateral relations, but also the position of China. If China made great efforts to give more religious freedom to its people, then things could change. But I think, personally, the Holy See would never abandon the Catholic Church in Taiwan. Taiwan is really a free country, [where] any people can choose any religion they believe in. The government never puts its hands in religious matters—and this freedom is not enjoyed everywhere in the world today.