F.A. Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom (1944) is often portrayed as a mid-20th-century economist’s restatement of a 19th-century case for unreconstructed laissez-faire economics. Anyone who has read the text, however, knows that this is a serious misrepresentation of Hayek’s most famous book. Road is in fact a much more complicated piece of writing, with messages as relevant for an early 21st-century world as it was when the book was first published 80 years ago.

It takes only a few pages of reading Road before one realizes that the book’s agenda cannot be caricatured as a mere laissez-faire tract for true believers. For one thing, Hayek draws extensively on history, philosophy, and sociology, as well as authors such as the historian Lord Acton and the political philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville whose intellectual priorities could not be described as those of an economist.

Hayek himself characterized Road as a “political book.” In later life, he suggested that its political character helped discredit him as an academic economist among his peers. Hayek lived during a period in which scholars who penned overtly political texts were regarded in universities as déclassé—unless, of course, the academic’s name happened to be John Maynard Keynes: the Cambridge economist who had been intervening regularly in domestic and international political, economic, and policy debates since writing The Economic Consequences of the Peace in 1919.

There are also areas in which Road is willing to accept state intervention into the economy in a manner that most 19th-century liberals would not have countenanced. Hayek spoke, for instance, of the legitimacy of a state-provided safety net, albeit one more restrained in scope than the behemoth welfare states that prevail throughout Western nations today.

Such recommendations were made against a more general background of a willingness on the part of Hayek and other prominent European classical liberal economists like Wilhelm Röpke, Walter Eucken, Jacques Rueff, Luigi Einaudi, and Franz Böhm to remake the case for market liberalism for a world quite different from pre-1914 Europe. As early as the mid-1930s, many classical liberals had insisted that it was insufficient simply to repeat 19th-century free market orthodoxies. This imperative contributed to the publication of Road but also books like Röpke’s bestselling The Social Crisis of Our Time (1942) and Jacques Rueff’s L’ordre social (1945).

The focus of these texts differed significantly from Road, however. Röpke’s text placed a much stronger emphasis than Road on the cultural roots of the breakdown of liberal civilization throughout Europe. By contrast, Rueff was more attentive to questions of monetary theory and monetary policy. What these texts shared was the conviction that classical liberalism had to adapt to a new set of political and economic conditions that favored interventionism and that seemed unlikely to dissipate in the near future.

These and other themes were further discussed at the first meeting convened by Hayek with some assistance from Röpke of what came to be called The Mont Pelerin Society in 1947. In his “Opening Address to a Conference at Mont Pelerin” to the assembled economists, historians, and journalists, Hayek said the following:

The basic conviction which has guided me in my efforts is that, if the ideals which I believe unite us, and for which, in spite of so much abuse of the term, there is still no better name than liberal, are to have any chance of revival, a great intellectual task must be performed. This task involves both purging traditional liberal theory of certain accidental accretions which have become attached to it in the course of time, and also facing up to some real problems which an over-simplified liberalism has shirked or which have become apparent only since it has turned into a somewhat stationary and rigid creed.

Among the “accidental accretions,” Hayek made clear, was a wariness about Christianity that had characterized much of continental classical liberalism. More generally, however, Hayek believed part of the challenge for contemporary classical liberalism was to expand its disciplinary horizons beyond economics. He also thought it important to understand how freedom was being undermined in ways that “an over-simplified liberalism” was insufficiently attentive.

This helps explain why Road, though written by a distinguished economist internationally known for his severe criticisms of interventionist economics and public clashes with Keynes in the 1930s, has less economics in it than informed readers might otherwise have expected. There is plenty in the book about how trends to economic planning, whether the outright collectivist version or the moderate Keynesian type, steadily corroded norms and institutions of liberty. The underlying logic of the Road, however, comes less from economics per se than from ideas expressed by liberal thinkers like Tocqueville in Democracy in America (1840) and subsequent speeches and texts during his time as an active politician during the reign of King Louis Philippe (1830–48) and the Second French Republic (1848–52).

Here it is important to recognize that Tocqueville was not as prominent a reference point in Western political discourse in Hayek’s time as he is today. Hayek, though, had become interested in Tocqueville for several reasons. These included Tocqueville’s treatment of the relationship between religion and liberty and why it manifested itself differently in America compared to Europe, where the two worlds seemed in perpetual conflict.

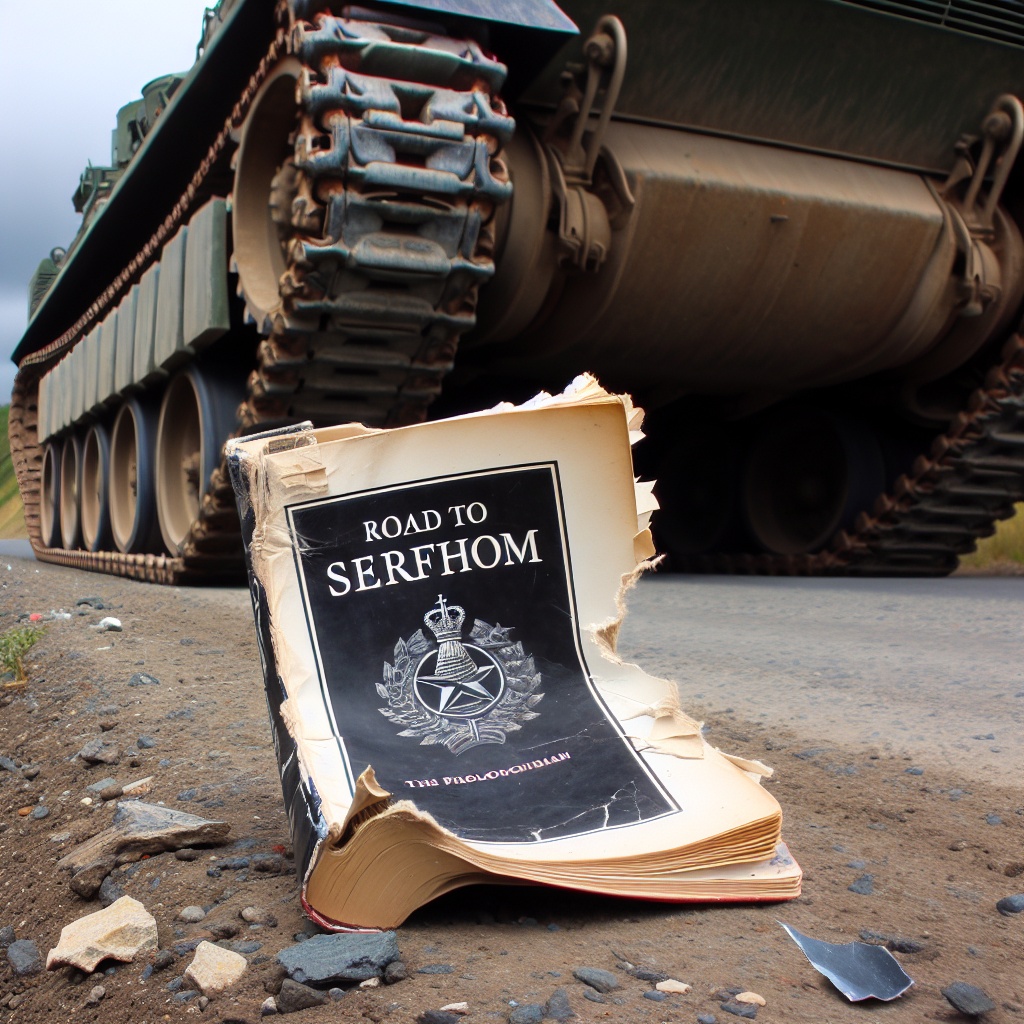

But Hayek was just as interested in Tocqueville’s diagnosis of how democratic societies could steadily move in distinctly illiberal directions, with much of the population not even noticing while others acquiesced in (and still others profited from) the same trend. The very title of Road to Serfdom draws upon Tocqueville’s observation in Democracy in America that some of the more enlightened people around him “have finally discovered the path that seems to lead men invincibly toward servitude. They bend their souls in advance to this necessary servitude; and despairing of remaining free, at the bottom of their hearts they already adore the master who will soon come.”

Neither Hayek nor Tocqueville had a deterministic conception of this drift away from liberty. Both saw, however, a rationale at work as people traded liberty—and then steadily increasing amounts of freedom—for other things they valued. Those “other things” could range from greater equality in the distribution of wealth to more state-provided economic security and stability, or the hope that the turmoil of economic life could be managed more efficiently from the top down by ostensibly apolitical technocrats and experts. In any case, the diminution of liberty is far removed from the suddenness of a military coup d’etat such as that experienced by Tocqueville in France by President Louis-Napoleon in 1851, or seizures of power akin to that staged by the Bolsheviks in Russia in October 1917 or the National Socialists in Germany between January 1933 and June 1934

In a way, much of Road involves Hayek extending Tocqueville’s logic by showing the ratchet effect in the belief that it is worth giving up some liberty to secure other seemingly good ends. A key ingredient of Hayek’s argument is that as it becomes clear that the trade-off has not delivered what was promised (or has even produced negative unintended consequences), the response of those advocating for, say, a more equal wealth distribution is not to concede that it was a mistake to diminish liberty. Instead, they invariably insist that they require more power—and therefore that society may have to accept less freedom—to achieve the desired goal.

By “liberty,” Hayek does not simply mean the freedom to make one’s free choices so far as they are compatible with the liberty of others to do the same, or freedom from the arbitrary wills of others. He also has in mind the rule of law: something that is indispensable for any free society. It is not for idle reasons that Hayek devoted an entire chapter of Road to the ways in which gradual shifts away from markets toward economic planning progressively compromised the rule of law. After all, interventionism that aims at rearranging the distribution of wealth cannot help but result in the government intentionally treating people unequally.

From 1944 onward, Hayek was to develop these neo-Tocquevillian themes in ways even more overtly focused on political and legal theory than Road. Examples include The Constitution of Liberty (1960) and his three-volume Law, Legislation, and Liberty (1973–79). Economics did not fade in its significance for Hayek’s understanding of the trials facing the free society. Political economy remained central to his interests. But having been marginalized from economic debates by the triumph of post-Keynesian ideas and the postwar shift toward an economics dominated by mathematics throughout the Western world, Hayek’s intellectual investment in extra-economic responses to the decline of freedom only grew from the 1950s until his death in 1992.

Therein lies one of the important lessons of Hayek’s Road for us today. Advocates of free markets naturally gravitate toward economic arguments. Road, however, reminds us that some of the more subtle threats to freedom proceed, as Tocqueville understood, from the willingness of large numbers of people to freely give up liberty for goals that are not at all utopian but are nonetheless unrealizable. Good economic policy is indispensable but not enough if we want to avoid Hayek’s Tocquevillian prognosis of freely chosen servitude.