While the long 19th century gave birth to a variety of intellectual movements, it also saw its fair share of anti-intellectualism. The fallout from the Second Great Awakening was one such example; this era of American religious life witnessed the rise of pietism and biblicism, both of which called into question the value of both classical theological education and church history as a guide to biblical interpretation.

In the early 1800s, large crowds gathered at encampments throughout upstate New York, with many traveling long distances to witness great preachers deliver long and stirring sermons on hellfire and damnation. Among the most popular of the orators was Charles Grandison Finney (1792–1875), a former lawyer turned Presbyterian minister (despite many doubts about Presbyterian theology), and the most famous of the itinerant preachers of the Second Great Awakening. Finney, at a towering 6’3″, was known for his theatrical performances during these camp meetings and his controversial use of what was called “the anxious bench,” a practice of pressuring congregants to come forward during a service to experience conversion. Figures like Finney would come to determine the general direction of American evangelicalism and the role that big personalities—celebrity preachers—would play in it.

In many ways, Finney represented the culmination of pietistic trends working their way through the various Protestant sects. Pietism was a movement that originated in Germany in the 17th century with the publication of Pia Desideria by Jacob Spener and emphasized introspection and a turning away from the formal rituals of the institutional church. It was a reaction against scholasticism that marginalized formal worship in favor of small groups called “conventicles” and that saw no need for, or at least made secondary, the confessional standards of the Protestant churches. Pietism was effectively a way of doing religion on the fly, with personal conviction and feeling leading the way. As Daryl G. Hart details it in The Lost Soul of American Protestantism, the legacy of the Second Great Awakening and its pietist leanings is an anti-creedal, anti-clerical, and anti-ritual bias seen in much of evangelicalism today.

In America, pietism grew with biblicism, an approach to biblical interpretation that divorced the text from the commentary of church history. It sought to ignore what previous eras and the great theologians of the past had to say. Preachers who had no formal theological education, like Finney, argued that since neither Jesus nor the apostles had seminary training, neither did they.* All this produced a huge anti-intellectual tendency in the broader American culture that historian Richard Hofstadter traced back to this period. This combined with the disestablishment of state churches in the American project of religious liberty and a populist movement in American politics during the reign of Andrew Jackson.

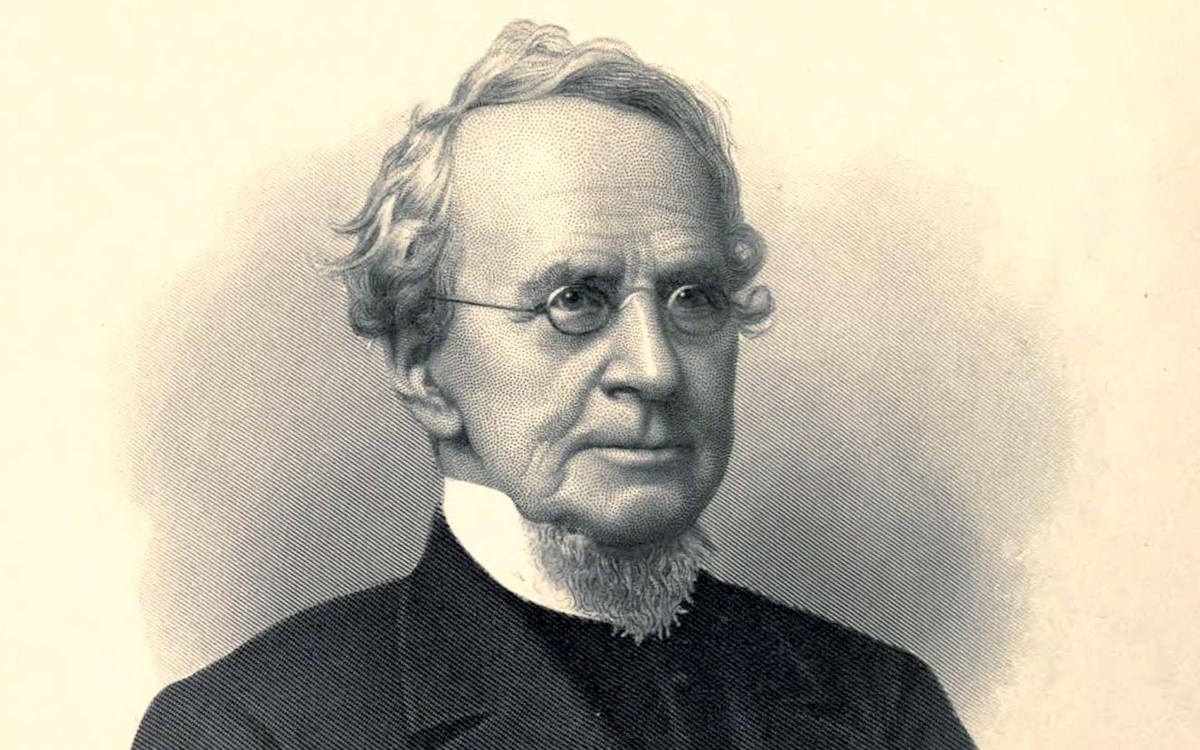

Enter John Williamson Nevin, a graduate of Old Princeton and professor at Mercersburg Seminary, the denominational seminary of the German Reformed Church in the 19th century. Nevin, together with his colleague Philip Schaff, constructed the Mercersburg Theology, a project of retrieving the classical Christian theological traditions of the Reformed and patristic periods. Nevin sought to bring back the intellectual heft of the Reformation to the Protestantism of his day. This relied on a catechetical approach to the faith and was expressed in High Church liturgical renewal. He opposed subjective introspection that was advocated by pietists in the Second Great Awakening and promoted what he called a “sacramental and educational religion,” which he believed was to be found in the confessions and catechisms of the Protestant churches. He dismissed men like Finney as quacks who had engaged in novel methods of conversion that required little more than histrionics to make up for their lack of theological grounding and pastoral skills.

Nevin displayed academic rigor in his theological debates, highlighting and drawing from both the Reformational traditions and the ancient church fathers. In fact, history played a significant role in his polemics with renowned Princeton theologian Charles Hodge over the Reformed doctrine of the eucharist. Hodge embraced a very symbolic view of the supper, while Nevin argued for the view held by John Calvin, one of a mystical presence mediated by the Holy Spirit. While Nevin’s engaged in a number of battles like these in his own day, his educational rigor, intellectual curiosity, and quest for history and tradition remain a blueprint for many Christians today seeking a Protestantism with more substance.

Nevin’s doctrine of the church also motivated him to write on questions of the church’s relation to the state. His ideas in this area developed over the course of his career, and he finally came to embrace a conception that drew both from his magisterial Reformed heritage and the German philosophical tradition. Nevin argued that there were two spheres in creation: a common sphere and a divine sphere. The common sphere was made up of kingdoms and rulers throughout all times and ages. This sphere was used by God to rule over His creation in a common way that kept creation from devolving into chaos. The divine sphere was that of the church, by which God revealed His will for redemption and salvation and realized it through the officers of the church who performed word and sacrament ministry. Nevin’s High Church Calvinism pushed him to make hard distinctions between church and state so as not to corrupt the role each one had to play in the natural order by confusing vocations.

Protestants, especially of the confessional kind, would do well to learn some of the lessons of Nevin and his career. On the one hand, Nevin was in ways limited by the intellectual trends of his time, including his frequent overdependence on German sources like Hegel, which he absorbed from the work of Schaff and Friedrich A. Rauch. He embraced Schaff’s idea of the historical development of the church, which some say led to his denomination, the German Reformed Church, to merge with the German Evangelical Synod in North America, later to be absorbed (through a series of further mergers) into what is now the United Church of Christ, one of the most liberal mainline churches in the U.S. I think most of that legacy of liberalization, however, is more the work of Schaff and his contribution to the Mercersburg project.

On the more positive side, Nevin’s engagement with the history of Christianity recovered both Calvin’s doctrine of the Lord’s Supper and a serious reliance on the Heidelberg Catechism, one of the traditional doctrinal standards for the Reformed tradition. As revivalism turned many away from the confessions and creeds of the church toward personal experience, Nevin pointed students and congregants to ecclesiastical documents that had already stood the test of time and provided structure and assurance for their adherents beyond mere feelings. Nevin also worked hard to rewire Protestants so they could view themselves as having an organic connection to the medieval and ancient church, as part of a Great Tradition. He criticized what he called the “Puritan theory” of church history that fostered a high level of skepticism about anything having to do with rituals and high sacramentalism.

Nevin is largely a forgotten figure today, relegated to seminary classrooms and to study by those interested in his project of theological retrieval. His struggles with his own tradition and his emphasis on high educational standards for the ministry are instructive for contemporary encounters with biblicism and pietism that remain so prominent in American religion. And his work on church-state relations are also instructive for those tempted to meld the two as part of the culture wars. Nevin in many ways was ahead of his time, and his intellectual rigor and engagement with classical sources of the Christian faith can provide a way forward for confessional Protestants today as they struggle to “contend for the faith which was once delivered unto the saints.”

* Ironically, Finney would go on to found Oberlin College and become a professor of systematic theology there. Perhaps not so, Oberlin is generally regarded as one of the most radical colleges in the United States today, having long ago cut away its more fundamentalist, biblicist roots.