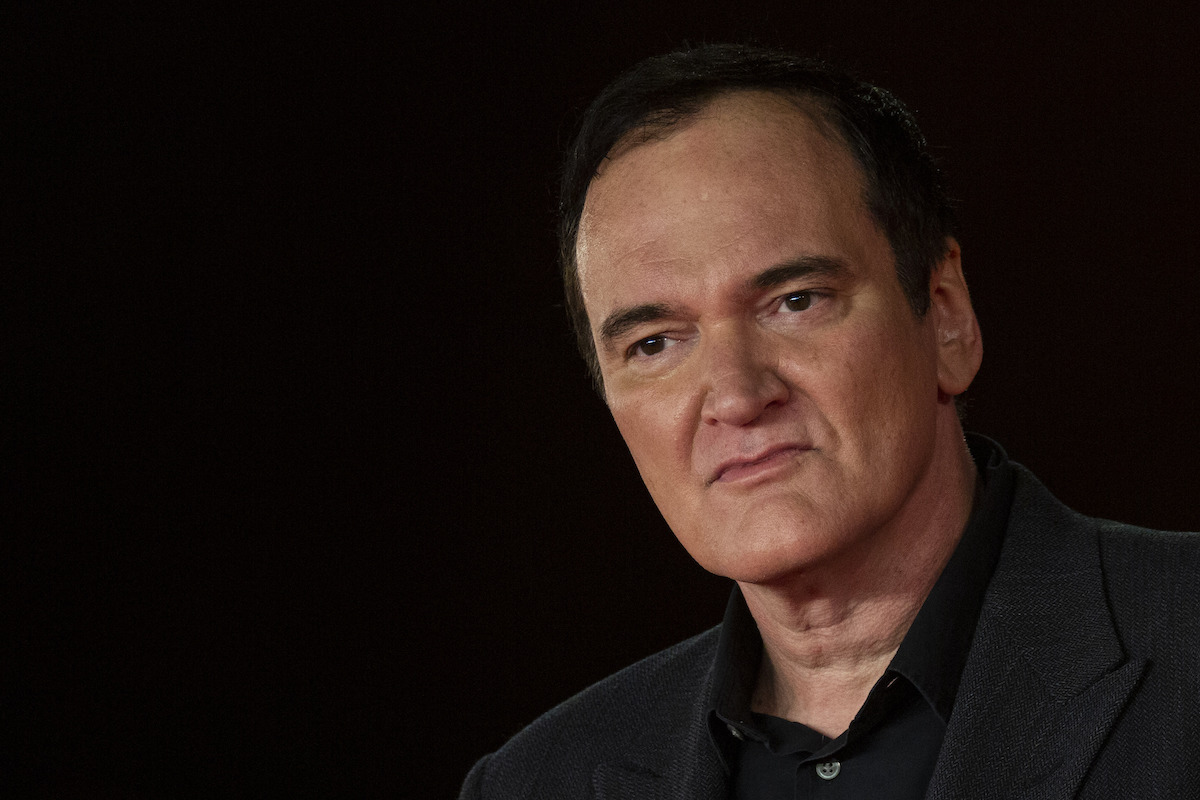

Hollywood has largely run out of artists and doesn’t seem able or perhaps even interested in producing movies that can hold a candle to the great achievements of its 100-year history. America still dominates cinema, but it has debased it to “content” that people “stream.” One of the few people left in Hollywood who can be called an artist is Quentin Tarantino, and he has a book out, Cinema Speculation, an attempt to recapture the artistic daring of his childhood years, the ’70s, the triumph of the New Hollywood.

Cinema Speculation looks like 13 essays on movies from Bullitt and Dirty Harry to Taxi Driver and Escape from Alcatraz. But Tarantino doesn’t write essays. He’s not trying his hand at movie criticism. He writes like he talks, trying to convey both his enthusiasm for the movies with which he grew up and his vision of cinematic art as a perfection of the American experience of freedom.

Movies are supposed to do two things at the same time: to amaze people such that they become an audience, suffering the same emotions together, losing themselves by following the story; and to surprise audiences with new possibilities or problems in American life, new protagonists held up for the nation’s admiration or shock. This goes far beyond entertainment but not beyond having fun.

This experience of cinema was Tarantino’s introduction to America as a child, and it is also the way he introduces his audience to his reflections on New Hollywood, with an autobiographical note. He never had a father or anything Americans would recognize as the ordinary middle-class family. His mother introduced him to cinema as a child. It’s the only life he knew or knows. Moreover, he became an American and a movie lover in the ’70s, the craziest time in America.

Another way to look at that troubled era, especially for a child who didn’t know any different, is that the experience of freedom was exhilarating. This was the one time in the 20th century when it was no longer clear what America was all about. You could do anything or at least see anything on screen. Adults would be as surprised or shocked as a boy when they saw Steve McQueen as Lt. Frank Bullitt look cool and do death-defying car chases. Or when Clint Eastwood as Inspector Harry Callahan face off against a serial killer in a lawless San Francisco. Heroes emerged in a lawless world.

Tarantino is defined as an artist by the tension one sees in the cinema of the ’70s between artists and audiences. On the one hand, the increasingly gloomy, not to say nihilistic exploration of the misery of that period in American history, the dead end of the path of authenticity or meaning. On the other, the rare moments of hope in that suffering. Above all, Rocky. Tarantino reports from the scene:

Everything about Rocky took audiences by complete surprise. The unknown guy in the lead, how emotional the film ended up being, that incredibly stirring score by Bill Conti, and one of the most dynamic climaxes most of us had ever experienced in a cinema.

I’d been to movies before where something happened on screen and the audience cheered. But never—and I repeat—never—like they cheered when Rocky landed that blow in the first round that knocked Apollo Creed to the floor. The entire theatre had been watching the fight with their hearts choking their throats, expecting the worst. Every blow Rocky took seemed to land on you. The smugness of Apollo Creed’s superiority over this ham and egg bum seemed like a repudiation of Rocky’s humanity. A humanity that both Stallone and the movie had spent the last ninety minutes making us fall in love with. Then suddenly—with one powerful swing—Apollo Creed was knocked to the floor on his back. I saw that film around seven or so times at the theatres, and every single time during that moment the audience practically hit the ceiling. But no time was like that first time. In 1976 I didn’t need to be told how involving movies could be. I knew. In fact I didn’t know much else. But until then, I had never been as emotionally invested in a lead character as I was with Rocky Balboa and by extension his creator, Sylvester Stallone. Now that type of audience innocence would be practically impossible to duplicate for somebody just discovering the movie today.

Of course, Tarantino’s cinema is nowhere near as heartwarming as his description of Rocky. “My dreams of movies always included a comic reaction to unpleasantness.” He goes on: “I was convinced there was a place for me and my violent reveries in the modern cinematheque.” He seems to want to reproduce in each of his films the craziness of the era in which he grew up before he gets to catharsis. Moreover, he doesn’t want artists to collapse into conformism. This is why the ’80s, a time most Americans remember fondly, terrify Tarantino. It was the beginning of the collapse of art, and he seems to think of it as the cause of the Hollywood we see nowadays. Tarantino complains about directors making compromises in that period:

Now I wasn’t a professional filmmaker back then. I was a brash know-it-all film geek. Yet, once I graduated to professional filmmaker, I never did let “they” stop me. Viewers can accept my work or reject it. Deem it good, bad, or with indifference. But I’ve always approached my cinema with a fearlessness of the eventual outcome. A fearlessness that comes to me naturally—I mean, who cares, really? It’s only a movie.

There’s a contradiction in there, of course, since if it’s only a movie, it’s not worth dedicating your life to it. Tarantino is in the top tier of the hierarchy of American artists of his time and has enjoyed the rewards of that achievement. Somehow we all know movies matter, indeed that America used to go to the movies to behold visions of American freedom; it was a national passion. He reasons himself into this contradiction in order to defend art from political correctness—to defend the freedom with which he grew up from the increasingly moralistic identification of speech or any form of expression with violence.

This contradiction is also Tarantino’s implicit recommendation to artists. They must not take art too seriously—it won’t transform the world—but nevertheless should dedicate themselves to it wholly and daringly, as he did, or else they will get swallowed up in an increasingly conformist industry. But he makes it clear that if artists are to brave the censorship, they would first have to love the movies, like kids do when they fall in love with images. Then they mature somewhat and learn that it’s the protagonists, the heroes, whom they love. Then they can grow up enough to learn how to tell stories for an audience that also goes through that transformation, though without becoming artists. Somehow cinema is an education in American freedom.

Cinema Speculation is silent about what freedom is for, what purpose it serves. If it weren’t, Tarantino wouldn’t be able to defend artistic freedom, much less guide artists by his own example, because he’d be stuck as a partisan in a culture war that isn’t, at least so far, giving birth to new talent or new art. He’s very defensive about proving his liberalism, in the old “free speech” sense, which is a kind of evidence that he fears Progressive moralism censoring him or denying him an audience.

Tarantino’s defensive rhetoric is also evidence that he is still quite daring and looking to reach young artists, to help them free themselves from a kind of matriarchy. His appeal to violence and humor is an appeal to the weapons of the boy against institutional authority, saying shocking or sarcastic things to people who are nice but despotic. His appeal to the antiheroes of the ’70s is an appeal to rugged individualism, an old American recourse against conformism, a memory that freedom could be noble, and could be tragic, too. For my part, I hope young artists take a hint from Tarantino and become daring—that’s better than the ongoing Progressive destruction of art.